Finland's PISA scores are declining but does that denote failure?

What has happened to Finland's PISA scores?

Finland was once a global pace setter in the field of education.

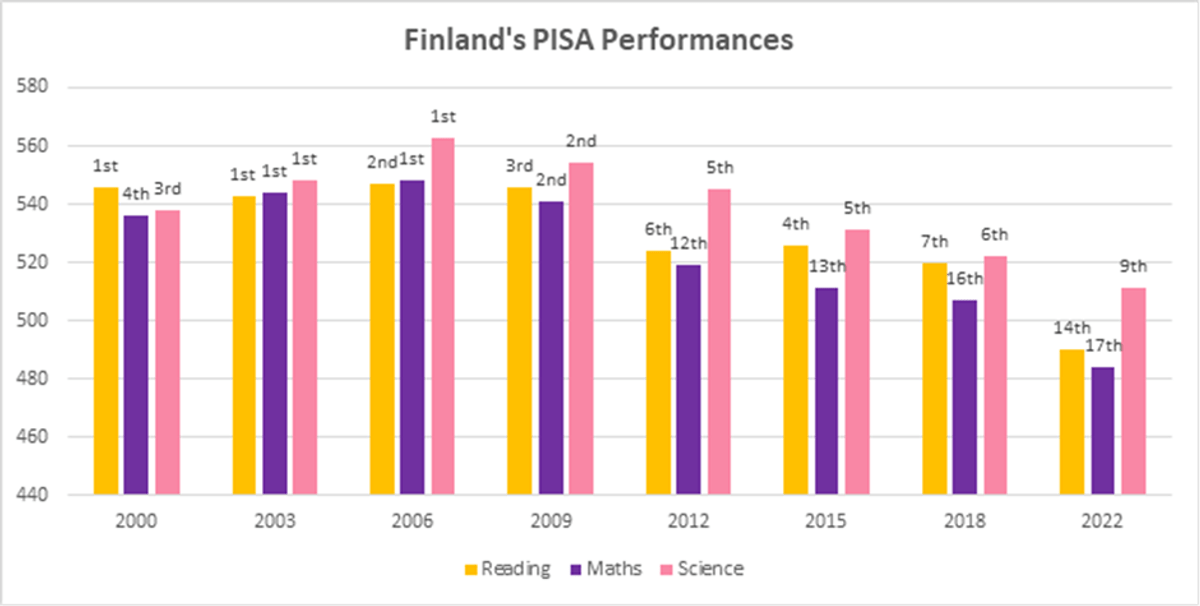

For close to a decade, it was among the best, if not the best, in all three subjects assessed in the PISA education survey – reading, science and maths.

But that was more than twenty years ago.

The most recent set of results confirmed the continuing decline in Finland's scores that started after 2006.

Source: OECD

It is not certain what lies behind the fall.

Some believe that its success was due to its historically centralised and authoritarian schooling system underpinned by economic growth.

The subsequent decline, they argue, is due in part to decentralising and student-centred reforms imposed during the 1990s.

Others have criticised that argument for being ideologically motivated.

So, that is the main debate surrounding the changes in Finland's PISA performances but that may be missing some other factors I think are at play.

Big picture changes in Finland and PISA

There has been a huge demographic shift in Finland.

Until the late 20th century, the country had little immigration.

In 1990, first and second-generation immigrants accounted for 0.8% of the population.

In 2000 it was 2% and by 2015 it rose to 6.2%.

The proportion of migrant students more than doubled in the ten years to 2022.

Bearing in mind that OECD research showed that in Finland migrant pupils performed worse than natives in international tests (though not necessarily national high stakes assessments), this shifting demographic is likely to have had an impact on Finland’s PISA results.

This relatively low performance could stem from challenges in terms of linguistic barriers, the disruption of moving to a new country (maybe as asylum seekers) and as the OECD study found, that immigrant students tend to be of lower socio-economic status than the non-migrant cohort.

But we must be wary of ascribing too much weight to this as the performance gap between immigrant and non-immigrant students is narrowing.

It must also be noted that the relative performance of immigrant students has been linked to the host country's immigration policy.

Those countries with more restrictive policies that favour highly skilled migrants did not have the same performance gap between non-native and native students as Finland.

And, while the changing nature of Finnish school population is relevant to the debate about its PISA results, there were other connected changes going on at the same time.

Support for learning in Finland has decreased

In the early 1990s, the total number of students attending lower and secondary vocational education was around 150,000.

Since then, the number of students in vocational upper secondary education alone has risen to more than 340,000.

At the same time, total state spending on education has fallen.

The effects of the country’s deep economic recessions in the early 1990s and again in 2008 led to public spending cuts across the welfare state but especially education.

In 1990, education spending took up 6.2% of Finland’s GDP. By 2022, that figure was 5.5%.

As a result of the cuts, schools had to merge, class sizes grew, teacher CPD was limited and staff numbers dropped.

Another by-product of the cuts was that socio-economic inequalities widened.

That left greater numbers of children in the more deprived groups struggling to perform at the same level as their less disadvantaged classmates.

In the early 2000s in Finland, only 7% of students were weak in mathematics. By 2022, that figure was 25%.

So, while teachers in Finland are highly educated (they are required to have master’s level qualifications) and widely respected in Finnish society, it appears that they are being asked to do more with less.

Is Finland's core curriculum in step with PISA?

Finland’s national core curriculum which came into effect in 2016 is designed to give students the skills and competencies politicians believe they need to engage fully in its modern society.

The new curriculum uses cross-curricular skills to strengthen students’ autonomy, help them become “good, balanced, and enlightened humans” and live in a sustainable way.

This ‘integrated interdisciplinary teaching and learning’ decreased teaching hours in maths and science and put more emphasis on arts and physical activity.

While these curriculum reforms were made with students’ (and society’s) future in mind, they are not directed at producing the skills assessed by the PISA framework which are focused on problem-solving by applying learnt skills.

Does this mean Finland is not trying to meet PISA standards?

According to Pasi Sahlberg, a leading figure in Finnish education policy, Finland is not guided by PISA results and will not use them to trigger reform.

He believes the country will meet the challenges of the future while still focusing on generic skills and traditional subjects through areas such as digital literacy, learning to learn and entrepreneurship as well as social and civic skills.

As Sahlberg said: “PISA tells us only a small part of what happens in education in any country. Most of what Finland does, for example, is not shown in PISA at all. It would be shortsighted to conclude by only looking at PISA scores where good educational ideas and inspiration might be found.”

Concluding thoughts on why Finland has slipped in the PISA rankings.

So, taking into consideration the economic factors that will have hampered education performances, the changing demographics that meant the proportion of lower performing students is growing and the curriculum reforms that have seen it break step with PISA, I don’t think Finland is doing so badly.

It is still in PISA’s top 10 globally for science, top 20 for maths and reading and all its scores are above the OECD average.

Arguably just as important, PISA background questionnaires show that the students’ sense of belonging at school has improved.

If we look beyond PISA, Finland is near top in the world in the latest PIRLS reading study and the TIMSS survey ranks its maths and science highly.

Finally, according to The Legatum Institute’s Prosperity Index its education system is second behind only Singapore.

Finland has challenges ahead for sure, but it remains a child-centred, research and evidence-based school system, run by highly professionalised teachers.

That’s pretty good in my book.

Dr Jonathan Doherty is a former teacher and education advisor who now works in teacher education at Leeds Trinity University. He is also chair of the National Primary Teacher Education Council.

As part of AQi’s work, we are inviting people from a wide range of viewpoints to engage with us on a wide range of topics. We welcome alternative views to help stimulate discussion and ideas. The views of external contributors do not necessarily represent the views of AQi or AQA.

Read More:

Estonia: A small country with big results

Singapore: Education pace setter looks for another gear

Massachusetts: The power of making education data public