International Approaches

Finland: Educating the whole child

Making equality of opportunity the defining objective of a nation's educational strategy

Why is the Finnish approach interesting?

Finland moved from average performance in the 1970s to become the highest performing OECD country in the noughties. This was achieved through a focus on equity with power and responsibility delegated to teachers, schools and municipalities. Finland has avoided curriculum standardisation, increased testing and the resulting approaches to accountability.

- Finland transformed its economy and educational system over 50 years.

- Equity is a strong theme in Finnish society. A comprehensive education system was created in the 1970s with the mission of equal educational opportunities for all.

- Power and responsibility is delegated to schools, principals, teachers and the municipalities within which are located.

- Teaching is one of the most highly respected professions. Competition to join highly-rated teacher training MA courses is fierce.

- External, high stakes assessment takes place at matriculation. Prior to this, student assessment is largely devised and implemented by teachers. An annual sample test is carried out nationally with the objective of supporting school decision making rather than applying centralised accountability.

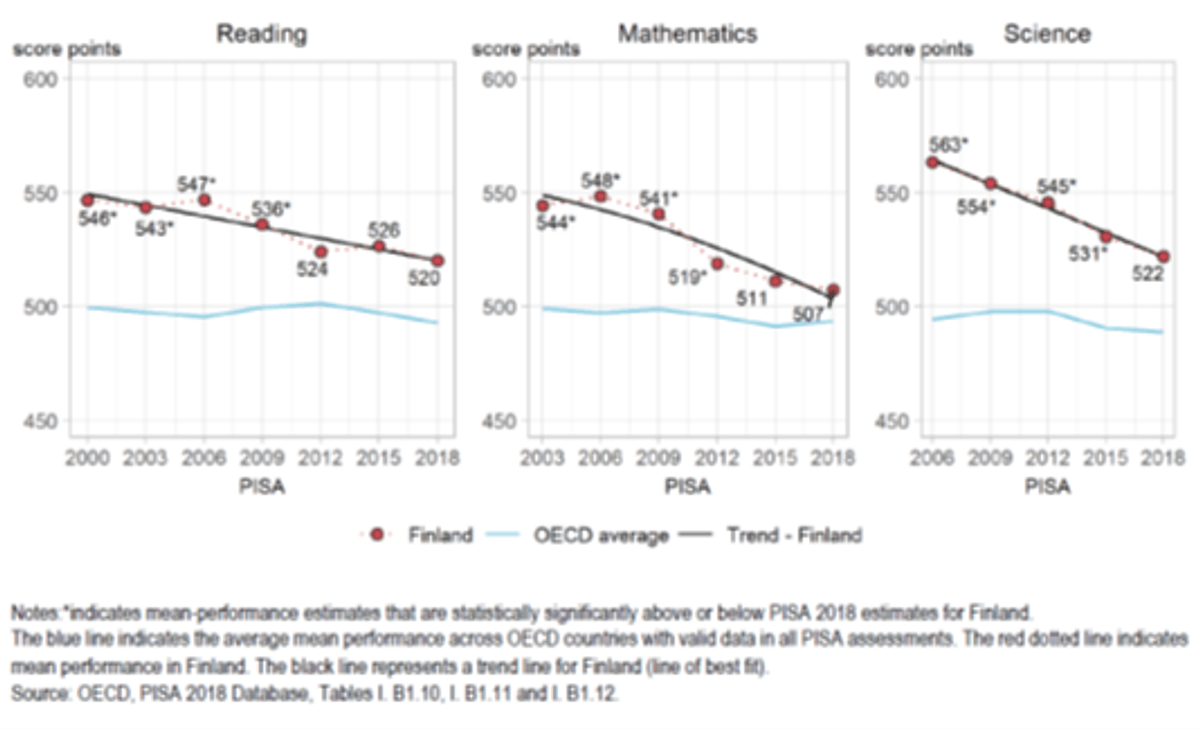

- Despite PISA scores slipping during the last decade Finland is still ranked a leading OECD country. Government has retained focus on teacher development and innovation to achieve improvements.

Finland has transformed both economically and educationally over the last half century

- Badly damaged by the war, Finland’s economy has moved from agriculture, forestry and heavy industry towards technology-driven knowledge industries.

- Rapid urbanisation: Finland went from 60% rural to 85% urban between 1960 and 2018.

- Innovation is both a national value and economic practice – Nokia created an electronics and telecommunications industry for example – and R&D spending is a high percentage of GDP.

- Near the top of World Economic Forum rankings for global competitiveness and preparedness for change.

- Extensive welfare systems and top of the UN’s World Happiness ranking in 2021.

In the 1950s…

Finland’s educational attainment level was similar to Malaysia and Peru and significantly behind that of neighbouring countries.

But performance in international student assessment studies leapt between the 1980s and 2000s:

- Consistently average performance until late 1980s.

- Since late 90s, amongst the top performing nations in TIMSS, PIRLS and PISA.

- Over the last decade, scores have slipped though remains near the top.

Over the last half-century we have developed an understanding that the only way for us to survive as a small, independent nation is by educating all our people. This is our only hope amid the competition between bigger nations and all those who have other benefits we don’t have.

Pasi Sahlberg, Professor of education policy, University of New South Wales

Finland’s PISA scores have slipped but remain high

PISA 2018 results by country/region - performance above the OECD average by subject area

Note: Data for China is only for Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu & Zhejiang

What is PISA? The Programme for International Student Assessment measures the ability of students to apply skills in reading, mathematics and science. It is done by testing a sample of students to reflect the wider population. The tests are designed to assess interpretation and the application of skills, not memorised knowledge

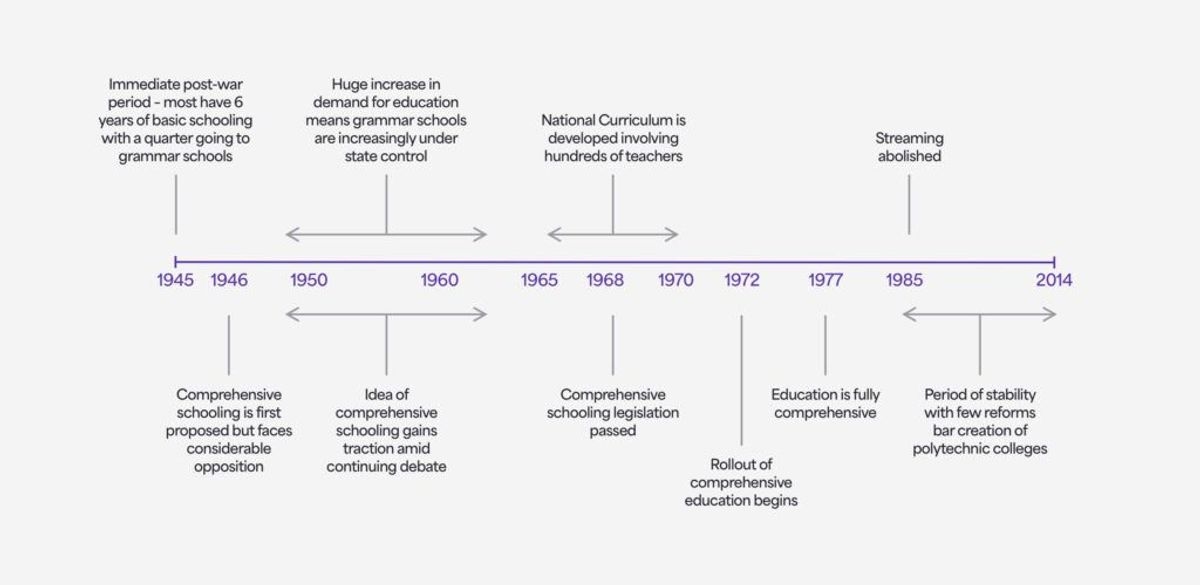

The peruskoulu comprehensive system, first proposed in 1959, was fully implemented in 1977

My challenge was to develop a plan that guaranteed this reform would ultimately be implemented in every Finnish community. There were lots of municipalities that were not eager to reform, which is why it was important to have a legal mandate. This was a very big reform, very big and complicated for teachers accustomed to the old system. They were accustomed to teaching school with selected children and were simply not ready for a school system in which very clever children and not so clever children were in the same classes.

Jukka Sarjala, Ministry of Education

(1970-1995)

The structures established in the 1970s have been central to the transformation of educational performance

- By 1979 all municipalities had moved to the comprehensive system and in 1985 streaming was abolished.

- The principle of equality of opportunity was fundamental – students from all backgrounds in the same system.

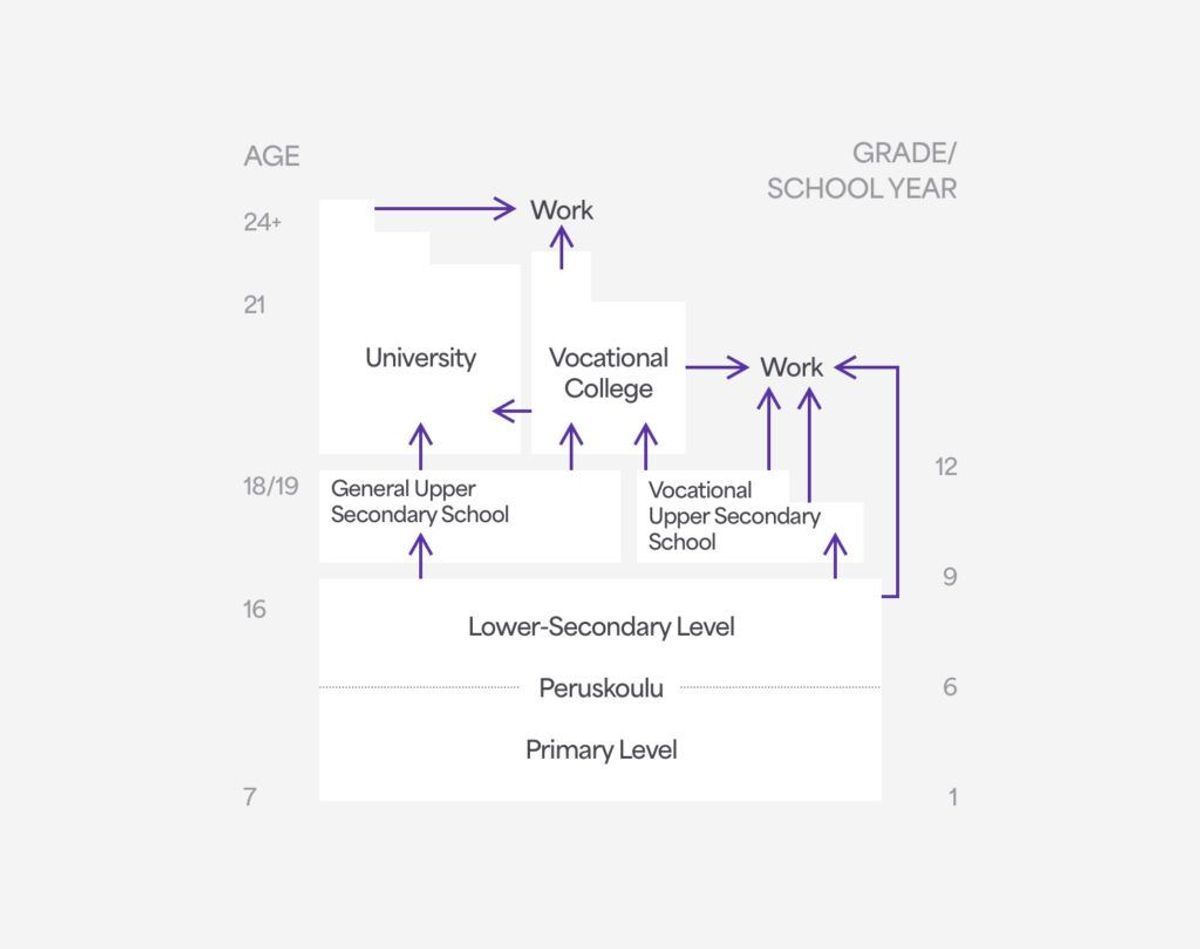

- Students start formal school at the age of 7. Until that age children do not face the pressures or structures of compulsory education.

- Great focus on supporting students with special needs resulted.

- Teacher education reform addressed the new challenges through increased research-based teacher education and professional development.

- Structures established to provide personalised career and development guidance for each student.

- Each school became a small self-governing institution with its principals and teachers leading decision making and innovation.

Finland has ignored the trends developed by the global education reform movement

As a countervailing force against the global education reform movement, the Finnish approach continues to reveal that creative curricula, professionalism of teachers, courageous leadership and high education systems performance go together.

Pasi Sahlberg, Professor of education policy, University of New South Wales

The 'global education reform movement' refers to the trend in many countries towards curriculum standardisation, the focus on core subjects, increased testing and use of data to measure progress and hold schools accountable.

Finland's approach has been very different:

- Strong focus on wellbeing and developing rounded citizens.

- Comprehensive system unaffected by competition based approaches.

- Decision making on implementation of curriculum, teaching and assessment delegated to schools, principals and teachers.

- Highly flexible approach to both curriculum and teaching approaches.

- The role and skills of teachers are central; teachers drive research and development.

- Limited national testing and control.

- Focus on teacher-led formative assessment.

The comprehensive school is not merely a form of school organisation. It embodies a philosophy of education as well as a deep set of societal values about what all children need and deserve.

Pasi Sahlberg, Professor of education policy, University of New South Wales

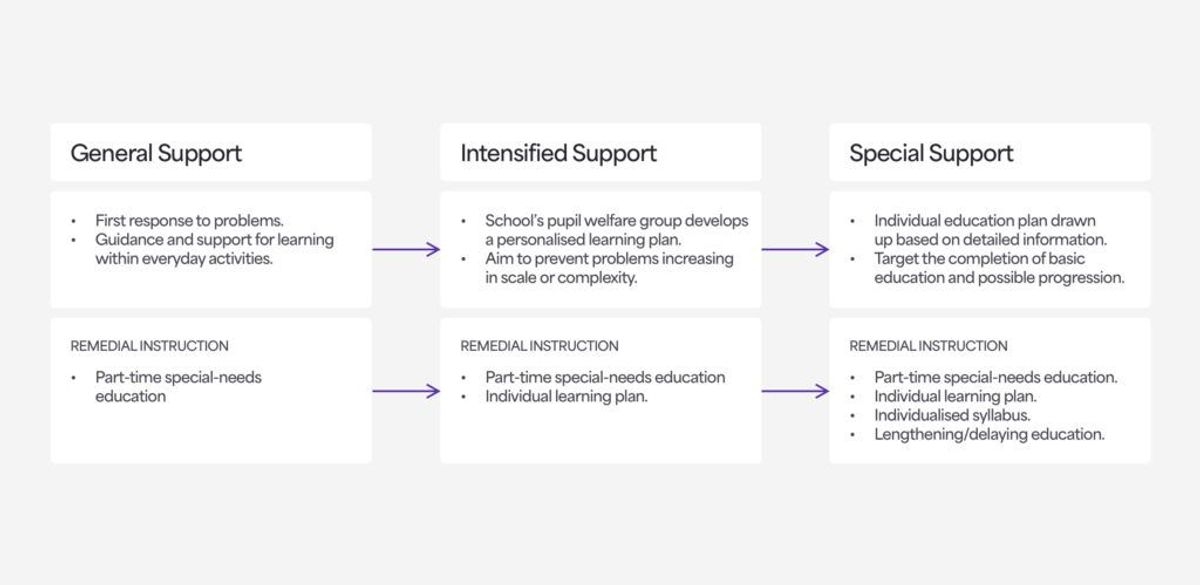

Students with special learning needs receive considerable support

- Special needs identified and addressed early

- 19% of peruskoulu students received special needs support in 2019; over 30% in 2012 before tighter budgets.

- Students are assessed individually. Support is flexible, adaptive, and based on long-term planning.

- Comprehensive schools have a multi-disciplinary welfare group which meets on a regular basis to discuss student needs.

Entering the teaching profession is highly competitive. Teachers have high status.

Highly ranked in society

- Ranked amongst the most respected professions above doctors and lawyers.

- Ranked particularly highly by young women.

Competitive, demanding Masters degree

- 1970s reforms moved teacher training from college to become a university-level masters degree. This 5 year course is challenging and wide ranging.

- Teacher education programmes are highly selective; only around 40% of applicants are accepted.

- The MA qualification is highly regarded and allows access to other high-value employment.

Rewards are not particularly financially driven

- Teacher salaries are lower than other professions, with limited opportunities for pay progression.

- But teachers have substantial autonomy and respect.

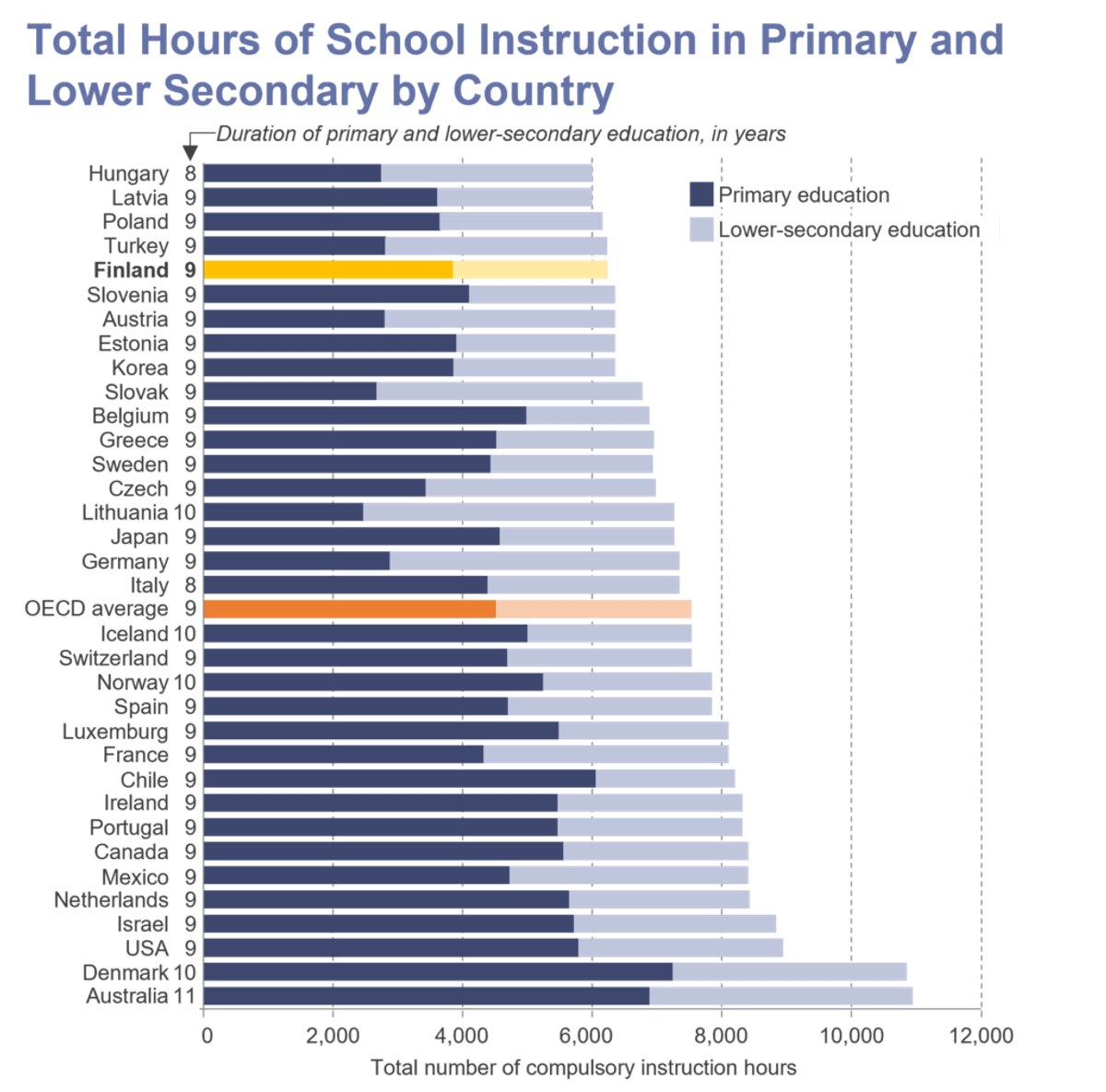

Teaching children for longer is not the Finnish approach.

More classroom hours can be seen as an obvious route to improving standards in core subjects.

In Finland teaching hours are lower than most OECD countries.

As you can see in the chart, there doesn’t seem to be a clear link between more teaching hours and learning outcomes by country.

Students start school later and finish earlier than in the UK or most other countries. There are 9 years of compulsory education.

Shorter school days mean that Finnish children have more opportunity for other activities: -Primary schools offer after school activities and recreational opportunities -There is also a strong network of NGOs providing sports and other activities for young people -2/3 of 10-14 year olds are members of one or more association

This reflects the emphasis on whole child learning and education embedded with wider community and society.

The Finnish curriculum is very decentralised. Teachers have flexibility in what and how they teach

The National Curriculum

- Set by the Finnish National Agency for Education, the curriculum contains objectives and core content for subjects and sets general principles and guidance.

- It is a broad, directional framework, rather than being prescriptive.

- Local leaving local authorities responsible for periodic evaluation of education quality.

- Curriculum reviewed approximately every ten years in collaboration with a wide range of stakeholders.

The Teacher’s Role

- Finnish teachers teach fewer hours than in other OECD countries but their role goes beyond teaching.

- Teachers have responsibilities for curriculum development. This is approved by the local education authorities.

- The power to influence the curriculum allows teachers to determine bespoke teaching approaches to match the needs of students.

- Assessment is an important responsibility of the teacher, embedded within the curriculum and teaching processes that teachers develop.

Students have more choice and independence from a young age

- Classrooms are learner centred; students play a role in designing learning activities.

- Students learn to assess their own learning, as early as first grade.

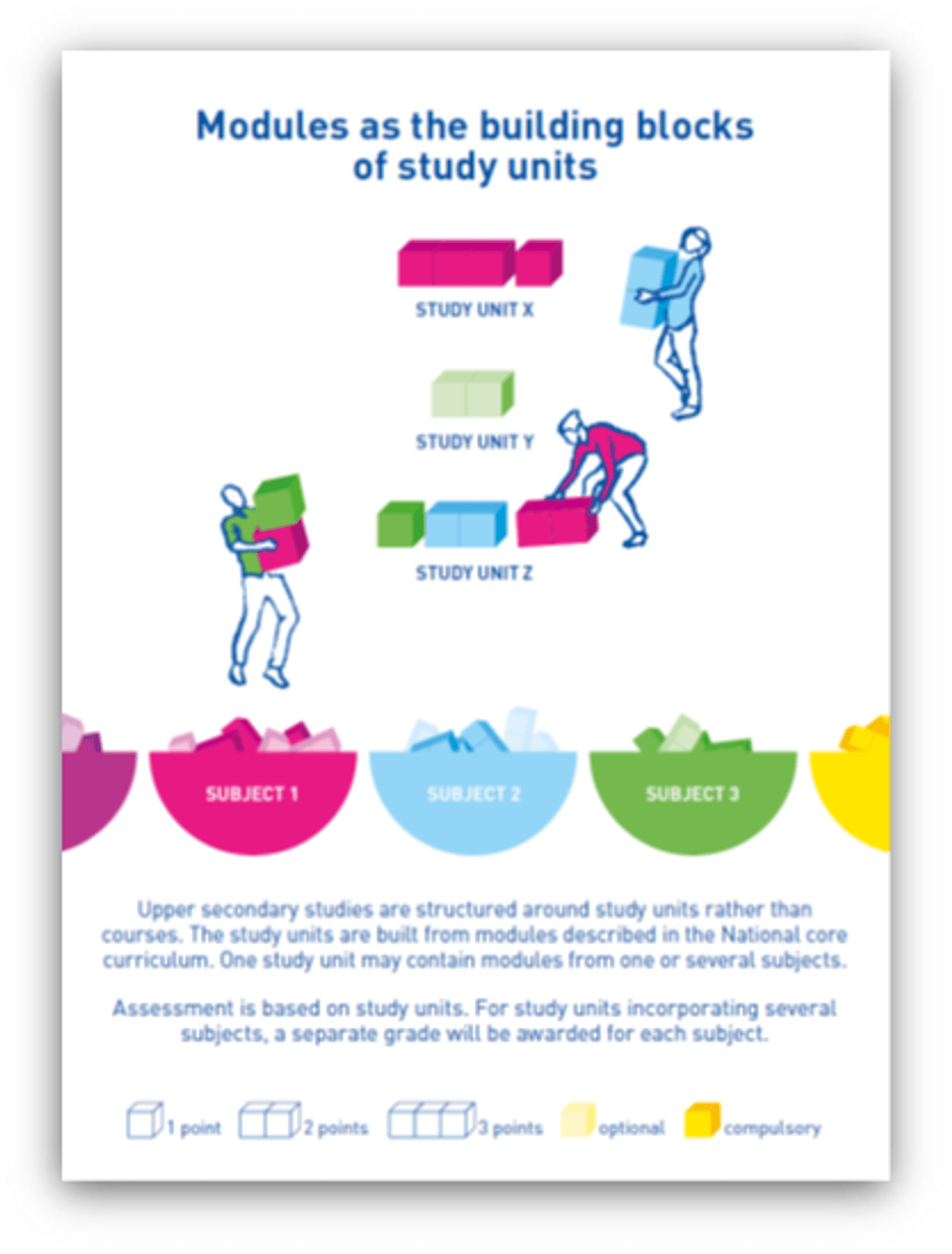

- By grade 10, students are expected to design their own individual study plan. Students proceed at their own pace in a modular structure.

The objective is to increase pupils’ curiosity and motivation to learn, and to promote their activeness, self-direction, and creativity by offering interesting challenges and problems. The learning environment must guide pupils in setting their own objectives and evaluating their own actions.

National Core Curriculum for Basic Education, 2004

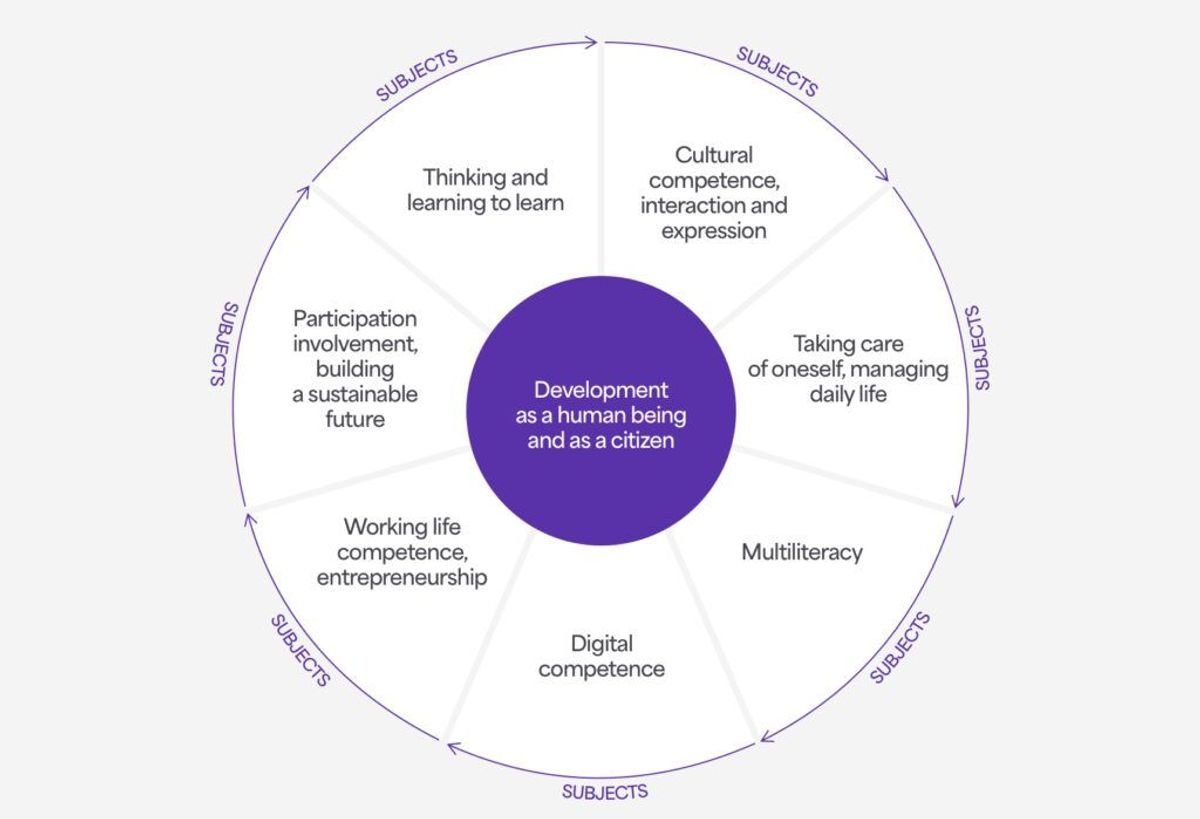

Recent reforms from 2014 are aimed at educating “good, balanced, and enlightened humans”

Developed four principles for effective promotion of learning and aimed to embed in the curriculum:

- Active involvement of pupils

- Meaningfulness

- Joy of learning

- School cultures that promote enriching interaction between pupils and teachers

Created “transversal competencies” – core objectives that cut across subject boundaries, for both basic and upper secondary education

Transversal competencies (promoting students’ growth as human beings and as citizens) demand: knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, will/volition

We are often asked why improve the system that has been ranked as top quality in the world. But the answer is: because the world is changing. We have to think and rethink everything connected to school. We also have to understand that competencies needed in society and in working life have changed.

Irmeli Halinen, Head of Curriculum Development, Finnish National Board of Education

Finland does not have an exam culture. Assessment is important but planned and carried out by teachers

- No national examinations until end of general upper secondary education, aged 18/19.

- Pupil assessment during peruskoulu is planned and carried out by teachers. Strong focus on continuous, diagnostic or formative assessment, with some summative assessment. This is planned and carried out by the teachers themselves.

- Teachers are well trained in multiple evaluation techniques during the 5 year MA programme.

- Basic education certificate from teachers determines students’ path into upper secondary education.

- Finnish Education Evaluation Centre (an independent organisation) carries out sample based external testing of around 10% of each cohort. This work takes place in 4 year national evaluation cycles.

- This data is used to evaluate progress of government policies and to provide insight for the evolution of strategy

- The research provides valuable insight to schools and some schools not included choose to benchmark their performance but the purpose is not national accountability.

There's no word for accountability in Finnish… Accountability is something that is left when responsibility has been subtracted

Pasi Sahlberg, Professor of education policy, University of New South Wales

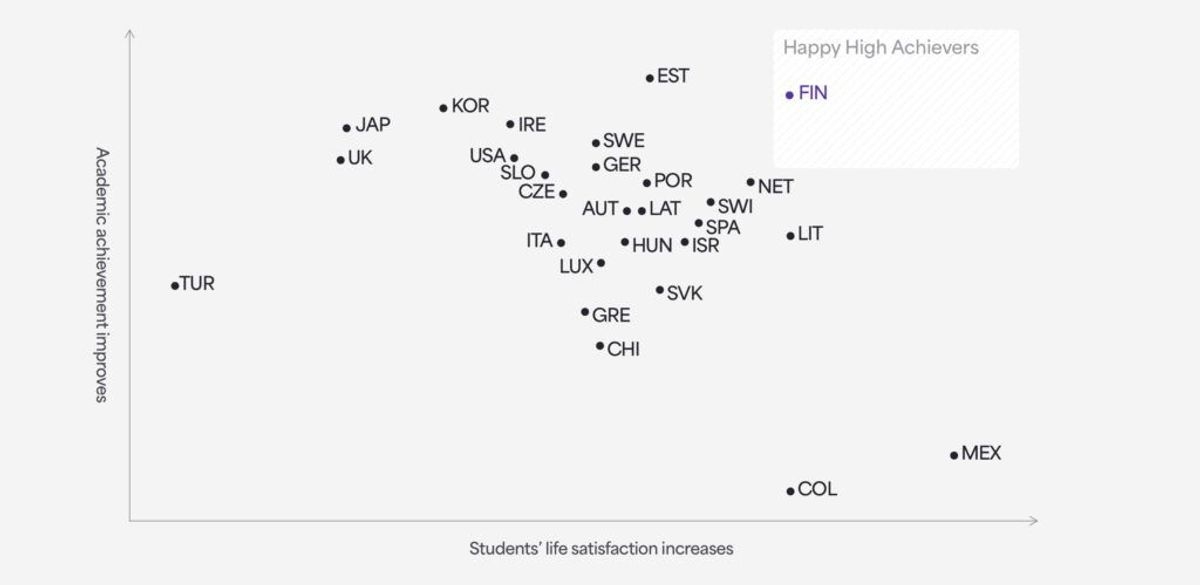

Finnish students are generally content as well as high achieving

- There is a multi-faceted view of educational success.

- “Children and young people feel well” is one of the governments four educational objectives laid out in 2020.

- Reducing differences in educational outcomes, discrimination and gender inequality are also explicit goals.

Student Life Satisfaction vs Academic Achievement

Finland stands apart on these metrics

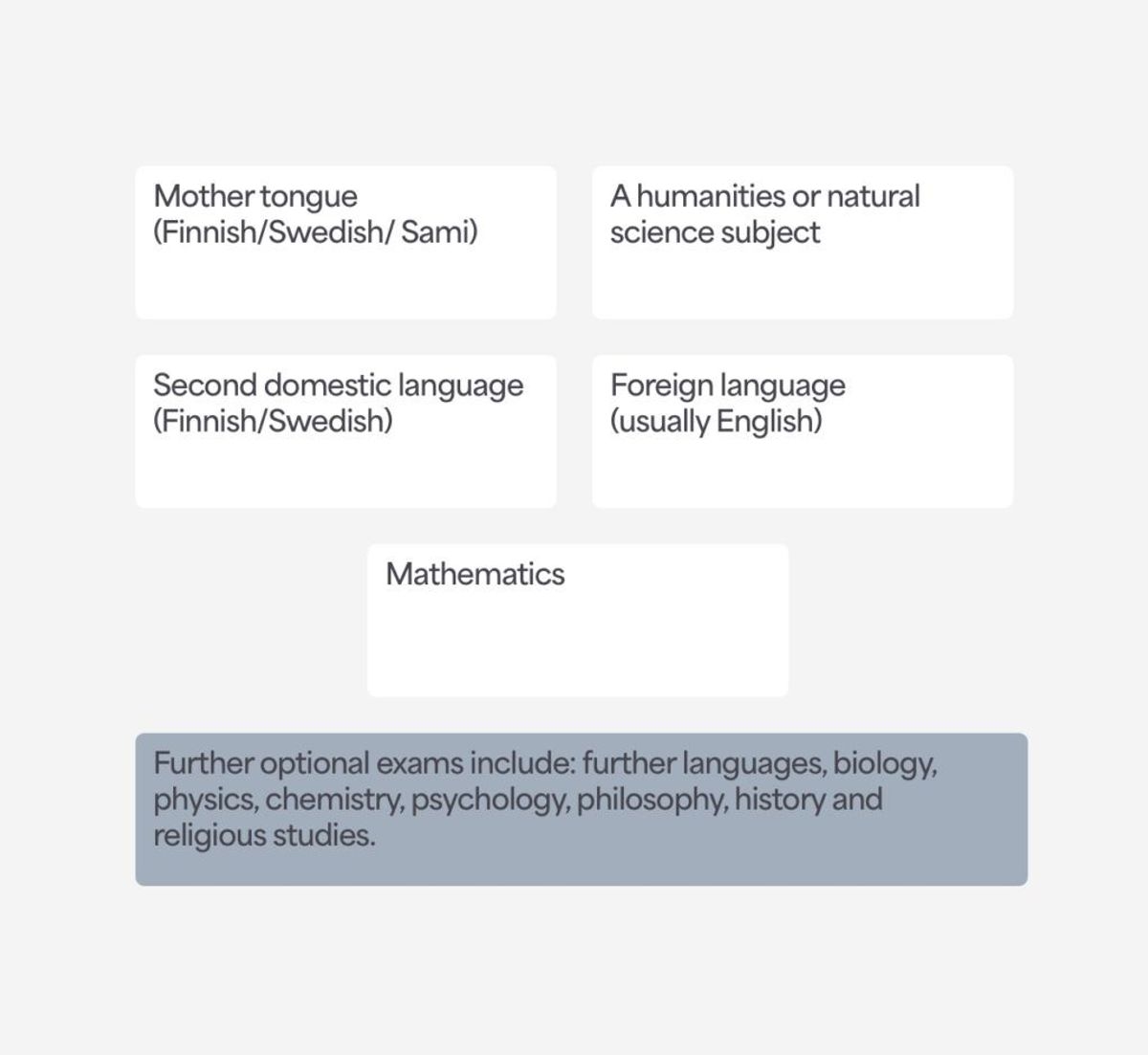

The summative assessment is the Matriculation Examination which is key to university entry

- The Matriculation Examination is taken by 18/19 year olds at the end of general upper secondary education.

- Students take a minimum of four tests to gain the matriculation certificate.

- The test in the mother tongue is compulsory. Then students may choose three from the remaining four options. Other subjects can also be added.

- Students have up to 6 hours to complete each exam. Tests involve extensive long-form writing.

- Subjects tackled in the exams are often topical and controversial issues of the day.

- 13% of Finnish students leave school without achieving an upper secondary school qualification, compared to 21% in the UK and around 25% in the OECD as a whole.

Wider societal factors contribute to educational success and new challenges

- Equity and public service are values that remain powerful in Finland.

- The Finnish child relative income poverty rate is one of the lowest in the world at 4%; the UK is 13% and the US 21%.

- The welfare system provided significant support to young families. Pre-school support is provided free by municipalities to ¾ of 1 to 6 year olds.

- Education is free from pre-primary to higher education as are school meals. Until secondary school, textbooks are free, as is transportation for students living at a distance from school.

- But now there are new challenges

Since the 1930s, new mothers have been provided with a start kit of essentials for new babies. Finland has one of the world’s lowest infant mortality rates.

Education is seen as an isolated island disconnected from other sectors and public policies. It is wrong to believe that what children learn or don’t learn in school could be explained by looking at only schools and what they do alone.

Pasi Sahlberg & Peter Johnson, Washington Post, 2019

New challenges

Finland’s performance in international studies has flagged in the last decade, particularly in PISA.

There are a range of potential factors which combine to reflect the new generation of pressures.

- National budget cuts have widened differences in provision across municipalities.

- Immigration has increased the number of people with foreign language backgrounds 10x since 1990 – now 8% population.

- Recent PISA tests show larger differences in reading performance between girls and boys.

- Measures of inequality in Finland have risen significantly since the 1990s.

- Finland has always committed to providing students with education in their native language (e.g. Swedish, Sami, sign language). With greater diversity of languages, this has become difficult to deliver.

- There is some evidence that students aren’t trying so hard in PISA tests.

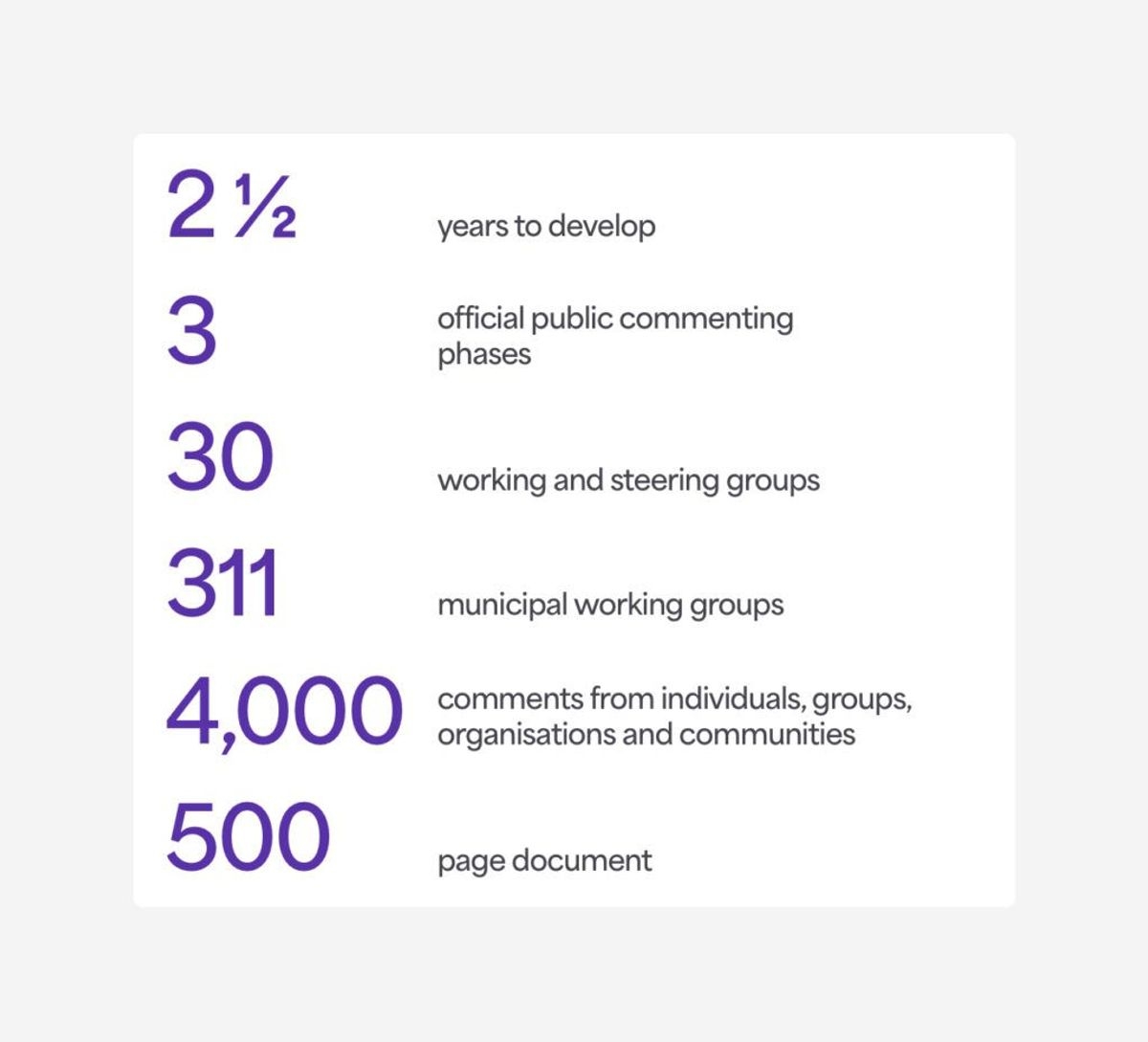

Policy evolves steadily and collaboratively as shown by the development of the new curriculum

- Initially triggered by routine review, the process took 3 years from 2014 to 2017.

- Students’ views were collected at the start and informed the whole process. Surveys were completed by 26% of students ages 13-16.

- The development was highly collaborative, including a wide range of teachers, principals and community stakeholders.

Finland’s reforms have evolved slowly and carefully over decades, have enjoyed broad and sustained political support across many changes in government, and are so intertwined with deep cultural factors that they are firmly institutionalised in the fabric of everyday life in schools. They are not the result of bold new policies or big programmatic initiatives that one can identify with a particular government or political leader.

OECD, 2010

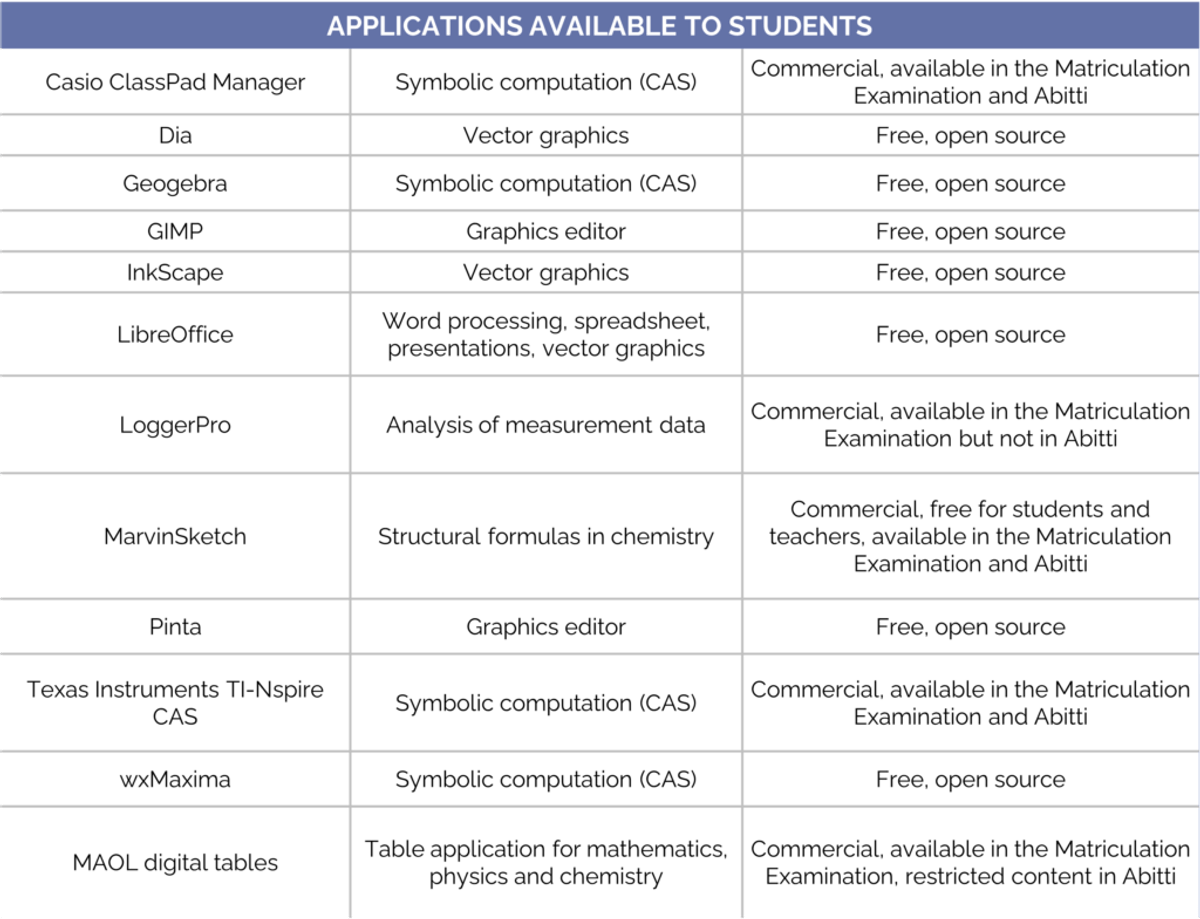

Since 2019, the Matriculation Examination has been fully digital

- Students can bring their own devices, and connect to a controlled environment to complete their assessments. Some evidence of a digital divide in Finland, but less so than in the UK.

- Teachers can use a separate system called Abitti for their own end of course assessments. Abitti works similarly to the Matriculation Examination so students can get used to the setup.

- Digital exams can include pictures, video, and audio, as well as a wider range of applications. For example, students can use statistical tools to analyse spreadsheet data.

7 Finnish findings

- Education systems can make significant progress without recourse to data driven accountability, competition or curriculum standardisation.

- The purpose of greater equity in educational outcomes seems to have helped deliver significant long-term improvements in outcomes. Focus on egalitarian public purpose can be powerfully motivating.

- Delegating responsibility and power to principals and teachers has been central to Finnish success. Habits and trust has been built up over several decades.

- Teaching is prestigious and Finnish teachers are highly qualified. The resulting professional commitment and respect are self-reinforcing.

- Assessment is used as a predominantly formative process and reflects the teaching approach rather than influencing it. The pressures and influence of high stakes exams are only felt through the matriculation exam taken aged 18/19.

- Wider egalitarian societal values, consistency of strategy and commitment to social support have helped create the environment for progress.

- Economic hits, budgetary constraints, language issues associated with increased migration and the impact of digital media bring new stresses that have probably contributed to declines in measured performance.

What is Finland’s secret? A whole-child-centered, research-and-evidence based school system, run by highly professionalized teachers. These are global education best practices, not cultural quirks applicable only to Finland.

William Doyle, Washington Post, 2016

References

Finland has transformed both economically and educationally over the last half century

World Happiness Report | Finland - Economy | Britannica | OECD – 1 | OECD – 2

Finnish Lessons 3.0 by Pasi Sahlberg

The peruskoulu comprehensive system, first proposed in 1959, was fully implemented in 1977

Students with special learning needs receive considerable support

Entering the teaching profession is highly competitive. Teachers have high status

OECD | National Center on Education and the Economy | Finnish Lessons 3.0, Pasi Sahlberg

Teaching children for longer is not the Finnish approach

Source: OECD TALIS data 2019; no UK data

The Finnish curriculum is very decentralised. Teachers have flexibility in what and how they teach

Students have more choice and independence from a young age

Finnish National Agency for Education - basic education | Alliance for Childhood EU | Finnish National Agency for Education - general upper secondary education

Recent reforms from 2014 are aimed at educating “good, balanced, and enlightened humans”

Finnish National Agency for Education - basic education | Finnish National Agency for Education - general upper secondary education | Alliance for Childhood EU

Finnish students are generally content as well as high achieving

Source: OECD / Finnish Lessons 3.0

The main summative assessment is the Matriculation Examination which is key to university entry

Kilpi-Jakonen 2017 | YLIOPPILASTUTKINTOLAUTAKUNTA | Lindblom & Räsänen, 2017 | OECD 2016

Wider societal factors contribute to educational success and new challenges

Washington Post | Sahlberg, 2012 | BBC | National Center on Education and the Economy | Finland - WID - World Inequality Database

New challenges

Big Think | Alliance for Childhood EU | Education GPS – Finland | OECD | OECD - Finland country profile 2020

Policy evolves steadily and collaboratively as shown by the development of the new curriculum

Lähdemäki, 2018 | Alliance for Childhood EU

Since 2019, the Matriculation Examination has been fully digital