Common trends have gained ascendancy in countries across the world in the drive to raise achievement levels through educational reform.

Increased testing, greater use of data, market-based competition, curriculum standardisation and performance-based accountability are the tools increasingly used by governments as they seek levers they understand to improve educational standards.

Finland has taken a quite different path - in many ways, the opposite.

Yet Finland is one of the highest performing European nations and remains an outstanding country in the field of education despite recent slips in PISA performance.

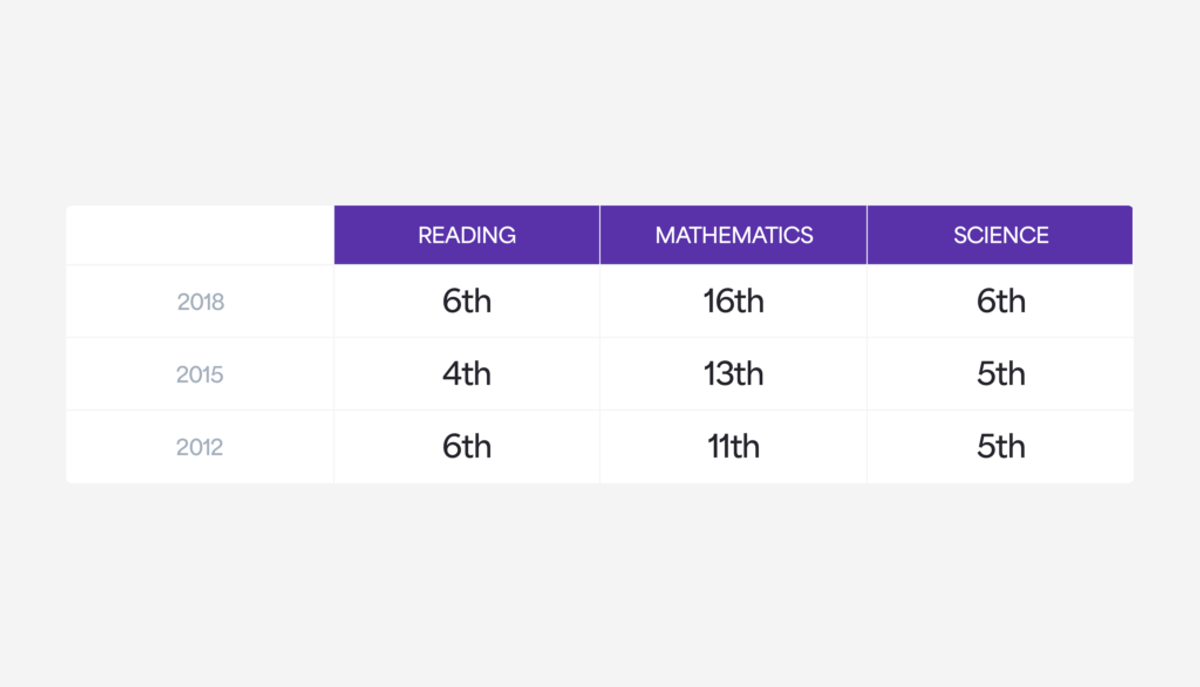

Finland's PISA Rankings Over Time

Source: OECD

Finnish success shows that there is another way. This is explored in this blog and in more depth in the longer Finland briefing paper.

What Finland doesn’t do

Finland introduced its comprehensive school system in 1972, completing national implementation in 1979. There are only a handful of private schools in Finland. Since the mid-1980s students have followed the same syllabi from primary until aged 16. Streaming was abolished and students have broadly the same learning goals.

Finland’s approach is egalitarian - not just in education but in its wider approach to societal development. The values that held force in post-war Britain, in the creation of the NHS, the social security system and public housing programmes, have retained greater prevalence in Finland.

Although there is a national core curriculum it is limited in detail and scope. The municipalities, school leadership teams and teachers have significant freedom in what they teach and how they teach it. Standardisation of curriculum and teaching approaches has not been implemented.

There is strong teaching of ‘core subjects’ – reading, writing, mathematics, science – but the breadth and diversity of the learning has been preserved. Finnish schools continue to focus on arts, music, physical education and regular playtime.

High stakes assessment through standardised external tests is limited to just one occasion – the matriculation exam (the Abitur) taken aged 18/19 by around 53% students who choose the academic pathway. The exams are focused on university admission.

Teachers carry out plenty of assessment. They have a strong academic grounding in diverse techniques and use assessment formatively to assist them in a student’s development rather than any relevance to national accountability. National tests are carried out on a sample of children each year, but it is left to the municipalities and school leadership teams to form conclusions.

What Finland does

The Finnish approach to educating its population is a holistic one stretching from the cradle to the grave. The importance of education is deeply embedded in society.

Over the last half-century we have developed an understanding that the only way for us to survive as a small, independent nation is by educating all our people. This is our only hope amid the competition between bigger nations and all those who have other benefits we don’t have

PASI SAHLBERG, PROFESSOR OF EDUCATION POLICY, UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES

The emphasis is on providing “opportunities for every citizen to study to their full potential.” Objectives are qualitative rather than quantitative, covering health, wellbeing and equity as well as more traditional academic performance.

Society has a strong egalitarian ethos. Significant support for children with special needs is made available to support their progress in mainstream school. Finland has the lowest variance between schools in student reading in OECD studies. Parents naturally turn to the neighbourhood school creating community commitment from all sections of society.

Since the potent debates about the move to a comprehensive system in the 1960s and 70s, governments regardless of political persuasion have maintained a steady vision for education, its role in society and in the development of the nation. There has been sustainable, evolutionary change based on consensus around equitable outcomes, implemented independently by principals and teachers at the local level.

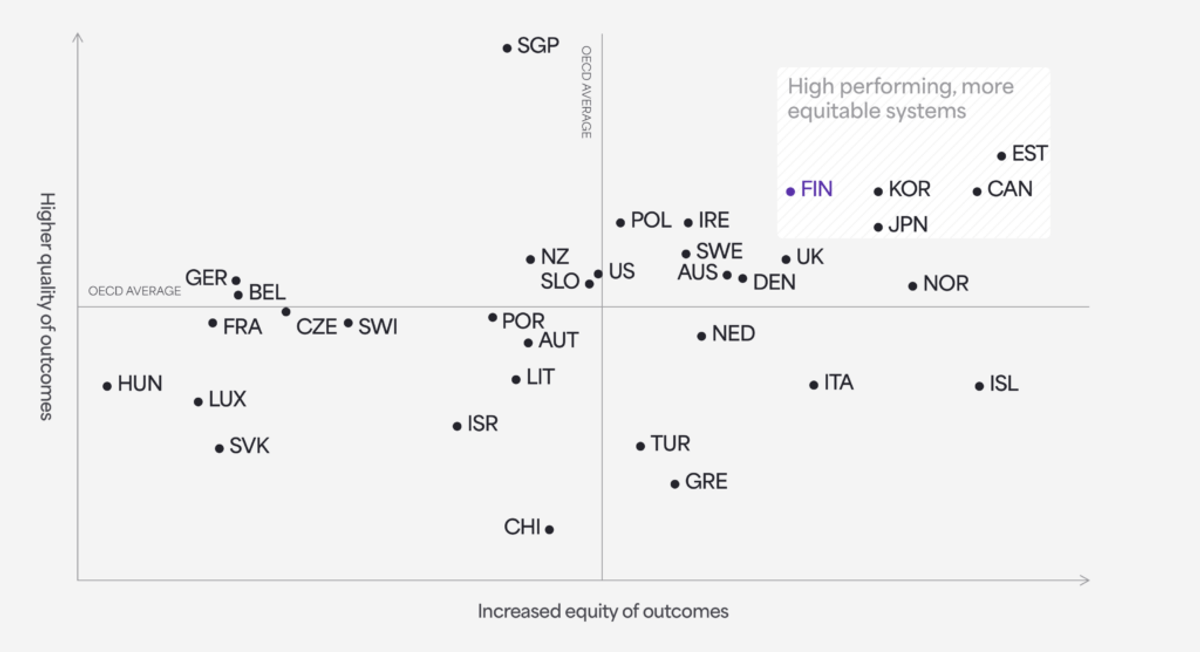

There does seem to be a correlation between equity and quality of outcomes – Estonia, Canada, Korea, Japan and Finland achieve this powerful combination according to OECD data.

Quality of Educational Outcome vs Equity of Outcome, 2018

Source: OECD

In Finland, limited central direction through a National Core Curriculum masks a clear, enduring strategy: to give control and responsibility to principals and teachers to optimally educate their students with holistic objectives. Principals and teachers are trusted to develop their own curricula, teaching approaches and student assessment.

Finland is highly selective in one aspect of its education system – its recruitment of teachers. The 5 or 6-year masters degree is challenging, heavily over-subscribed and trains teachers with the same rigour and depth of training as doctors or lawyers. It is also free. Teaching is a highly respected profession with the same values of integrity and independence associated with other elevated professions.

A deep understanding of areas such as learning theory, research, use of technology, interdisciplinary development and collaborative working is developed through the MA. Teachers are well prepared to make the development, adoption and spread of teaching innovation part of their work.

Are Finnish chickens coming home to roost?

Data from different international surveys shows that Finnish standards moved from an average performing nation in the 1970s to being a top performer in the first decade of the 20th century.

Since then, performance in PISA tests in particular have gently dropped in science, reading and maths. Though performance remains amongst the highest of OECD countries.

Equity of outcomes has declined (Finland is now average among OECD nations in this regard) and the number of low achievers has risen. Factors that may be contributing range from budget cuts following the 2007 financial crisis to the impact of digital devices on students.

The response of government and authorities has been to double down on the approach that has been successful: trusting the teachers, investing in teacher collaborations and embedding an inter-disciplinary curriculum rather than embarking on centrally directed targets or interventions.

A GERM alternative

Pasi Sahlberg, Professor of Education Policy at the University of South Wales, is the most prominent academic focused on the Finnish system.

He has created the acronym GERM (the Global Educational Reform Movement) to describe the trend towards external testing, data driven accountability and curriculum standardisation that has gained influence in the US, UK and other countries.

Sahlberg argues that despite the effort and resources committed, none of the countries adopting these approaches has yet raised performance significantly or caught up with the outstanding countries by international comparisons.

The work of Sahlberg, Hargreaves, Shirley and others poses hard questions about the direction taken by the ‘GERM’ countries which are in such conflict with the Finnish approach.

1. Teachers who decide or teachers who deliver?

Finnish principals and teachers are the core decision-makers about curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. They are professionals trusted to make the best decisions for their students and gain significant professional satisfaction as a result.

2. Standardised learning or personalised learning?

A centralised curriculum and performance targets bring clear numerical objectives but also standardised teaching, reduced classroom creativity and less empowered teachers. Finland’s more flexible framework allows personalised learning plans, is more inclusive and perhaps more effective.

3. Focus on core subjects? Or a wider view?

Core knowledge, reading, writing, mathematics and science are the focus with more time devoted in class. Finland’s approach has taken a broader view of a student’s learning across a wider range of subjects and also wider skills, values, character and personal development.

4. Can teachers have the same status as doctors and lawyers?

Teaching is a highly respected profession that attracts over 5x more applicants than there are MA places. As a result, teachers tend to be highly skilled and committed to their profession.

5. Collaboration or competition?

Finland emphasises the collective and collaborative in education: collaboration between different schools and their teachers; between schools and the community. This emphasises public service, egalitarian values and collective responsibility rather than the market-based approaches where different breeds of public school compete to win students based on performance results.

6. Assess for accountability or assess for the student?

When centralised assessment of student performance influences careers, pay or sanctions towards a school, this inevitably drives teaching towards the test rather than what is best for each student. Is the professional judgement of teachers and principals better able to assess the progress of students and target effort and resources?

School teachers and leaders are central to many of these questions in Finland. Their strength and capacity has been steadily built over more than three decades together with a relationship of mutual respect and trust established at both the local and national level. Emulating this core strength is a generational task.

These issues and more are explored in more depth in our Finland Briefing.

Read More on International Perspectives

Singapore: Global education pace setter looks for another gear

Estonia - a small country with big results

Massachusetts: The power of public education data

Singapore: Probably the best organised education system in the world

REFERENCES:

Finnish Lessons 3.0, Pasi Sahlberg, 2021

The Fourth Way, Andy Hargreaves and Dennis Shirley, 2009