Do learning styles differ between genders?

photo: Dainis Graveris/Unsplash

On GCSE results day Claire Thomson, AQA’s director of regulation and compliance, said identifying the cause of the phenomenon that sees female students outperform males would be speculation, but could be about societal expectations, differences in attitudes to work or even maturity levels.

Importantly, she added that this year’s GCSE and A level students should be “confident in the knowledge they have been assessed fairly and, really critically, importantly, when we are talking about males and females, they have been assessed anonymously.”

The recent growth of the gender gap in attainment

Examining the possible causes of the attainment gender gap takes us back to 1986 when GCSEs replaced O levels.

The new qualification differed from its predominantly exam-based predecessor in that it was more modular.

How has the gender gap in attainment changed over the years?

They were adapted over the years to contain more assessed coursework until Michael Gove’s reforms returned them back to a more linear model.

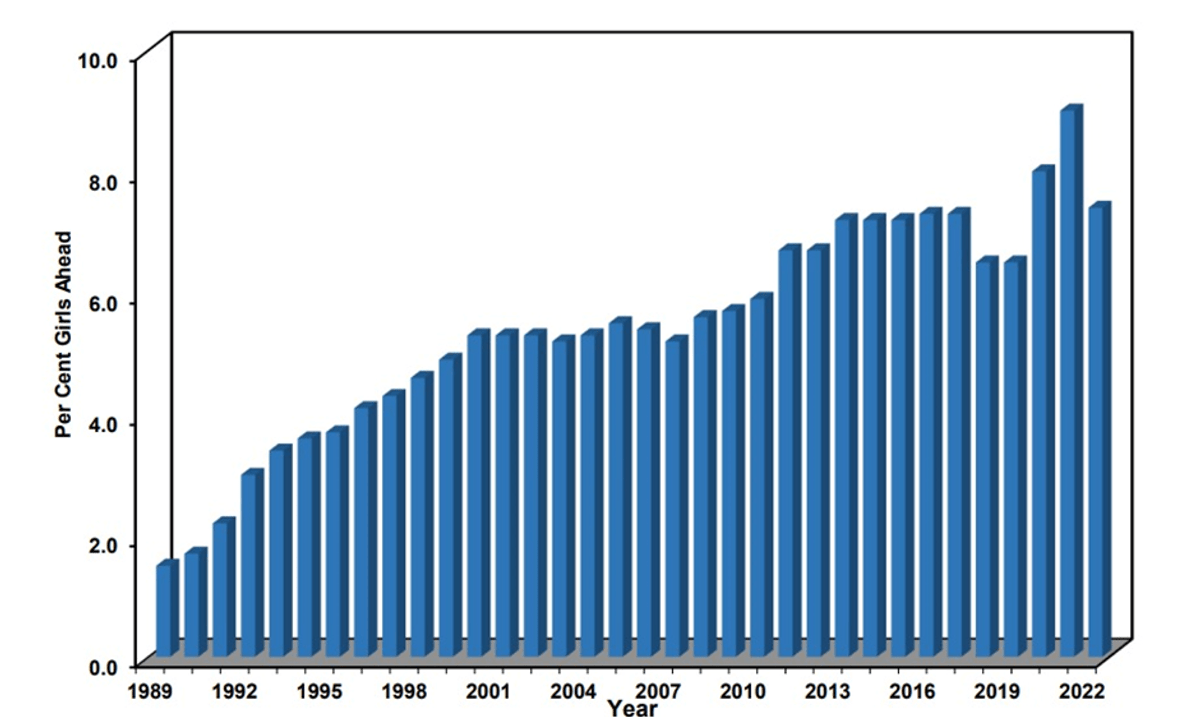

In 1989, the gender gap at the then highest grade A (A* was not introduced until 1994) was 1.5 percentage points in favour of girls. Some 24 years later it is 5.8pp at the equivalent grade 7 and above.

How did Teacher Assessed Grades affect the gender gap in attainment?

Although this is massive growth, it is not the biggest gap there has been.

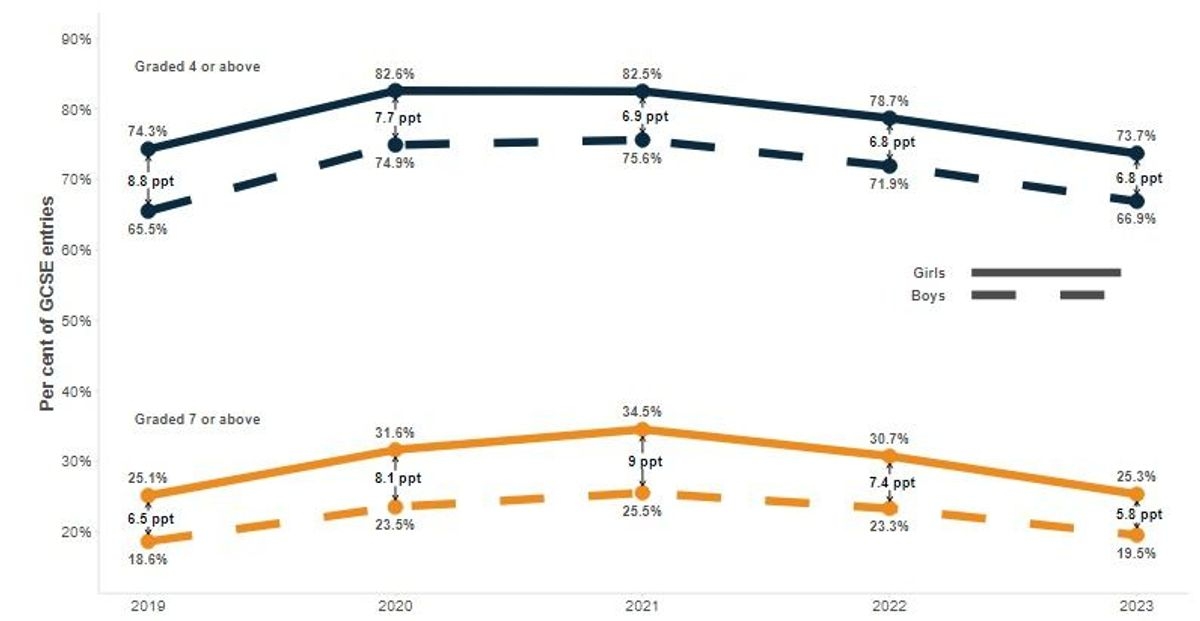

In 2021, the pandemic forced the suspension of exams and the use of Teacher Assessed Grades (TAGs) instead.

This reversed two years of the gap narrowing to send it to an all-time high of 9pp for the highest achieving students.

Did the return to exam conditions affect the attainment gender gap?

Interestingly, returning to full exam conditions sent it back down.

Achievement by 16-year-olds by gender in England - Source EPI/JCQ

Why GCSEs and Teacher Assessed Grades affected the gender gap

These startling statistics prompt two questions: Why did the gender gap grow so much after O levels were replaced and why did it grow faster with Teacher Assessed Grades?

Research appears to show that the introduction and nature of GCSEs could be part of the reason girls pulled away so dramatically.

O levels relied heavily on exams – which is said to suit boys’ style of studying – while the new qualification had more supposedly girl-friendly coursework until 2015 when Michael Gove’s GCSE reforms came into practice. The first exams under this system were in 2017.

Do boys and girls perform differently in exam conditions

The idea that boys perform better in traditional testing seems to be supported by statistics showing that, in 2018 and 2019, the attainment gap narrowed.

This connects nicely to research suggesting girls perform better at coursework.

Gender Gap in UK at Grade 7/A and Above source: Uni of Buckingham CEER

To back this up, attainment gap statistics reveal that the downward trend reversed when exams were suspended and the gap for the highest grades – 7/8/9 – grew from 2.5pp to 9pp in 2021 under TAGs.

Now pre-pandemic exam conditions are back, the trend has reversed again to 5.8pp – lower than 2019’s 6.5pp.

Why did girls get higher marks under Teacher Assessed Grades?

Another interesting statistic from TAGs was that in 2021, girls gained more top grades than boys in all but three subjects – physics, statistics and ‘other sciences’ (such as Environmental Science). In 2019 it was seven and this year five.

Getting to the bottom of this shift is complex.

Why do the different genders perform differently in assessments?

Some say teachers making those grade assessments may be more well-disposed to girls because generally, they mature earlier, have better verbal skills and are less disruptive in class.

There are also the gender stereotypes for studying styles that may have fed into teachers’ thinking.

Girls are said to perform better because they work on a more consistent basis rather than boys who are seen to cram before exams rather than study evenly throughout the year.

This may feed a subconscious perception that females are the better students.

Indeed, an Ofqual study found that in some subjects internally-set, internally-marked coursework benefited girls.

Teachers and students are not blind to the issue.

What studies into Teacher Assessed Grades show about the gender gap?

In post GCSE results interviews in 2021, teachers involved in handing out the TAGs said it was harder to determine grades for those with “inconsistent performance” - could that be the stereotype boy student who needs exams to close in before putting in the real effort?

One teacher said they had “lazy but smart” male students who “probably would have done better if they’d have been sitting an exam, because they would have risen to the occasion.”

Some students feared that personal relationships with teachers could affect their judgement – it would be easy to think the disruptive element may be judged most harshly.

Ofqual looked into divergence between teacher and test-based assessment and found that bias in teacher-assessed results in favour of girls or against boys was indeed more common than no bias or bias in favour of boys.

What we learnt about the gender gap from Teacher Assessed Grades?

So where does all of this leave us?

What we can take away from the experiment with TAGs is that they inadvertently exacerbated the gender attainment gap.

It reinforces the argument that the least unfair way to assess a student’s level of attainment is through anonymised, well-designed, and expertly marked exams.

Whether you arrive at school in a Bentley or 143 bus, once inside the exam hall everyone is level.

But let’s leave the last word to one of the students who took part in the 2021 Ofqual post GCSE interviews.

“I’d prefer to have just sat the exam and then everyone’s on the same thing, everyone’s in the same situation.

Read More:

GCSEs: Working harder for us than you may think

EPQs: Spark a lifelong love of learning

AI: Assessing performance claims