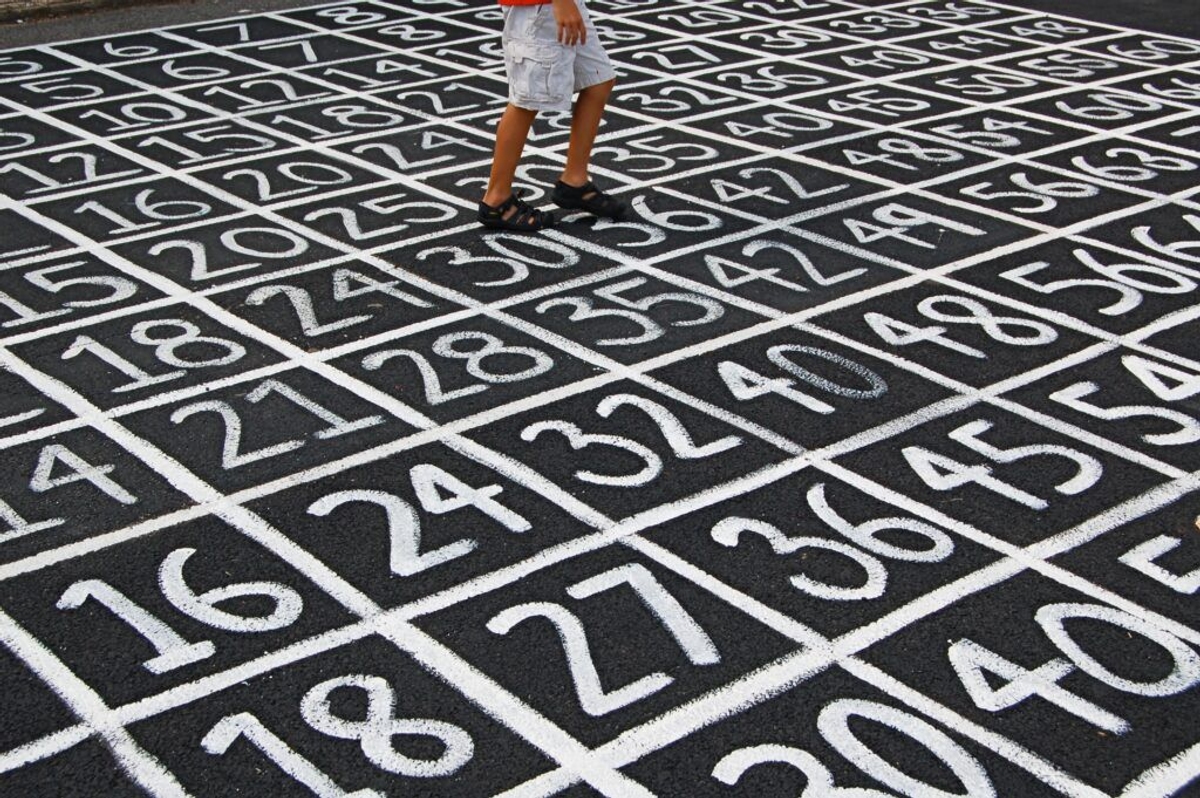

Numeracy can help us navigate modern society

In his first speech of 2023 Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called for a mindset change in education to “reimagine our approach to numeracy”.

Supporting the case for making numeracy a central objective of UK education, Mr Sunak outlined the need to upskill young people approaching the end of compulsory education.

“In a world where data is everywhere and statistics underpin every job, letting our children out into that world without those skills, is letting our children down,” he said.

With this sentence the PM identified numeracy as a much-needed life skill, essential for navigating employment opportunities.

Maths to 18, he said, will equip young people with the “quantitative and statistical skills” needed for the “jobs of today and the future” which are also the skills needed to confidently manage personal finances in later life.

The skills gap would be addressed by young people getting the grounding needed to work in data-rich environments.

In turn, the UK’s global competitiveness would be maintained by instilling confidence in those managing data intensive workplaces that there is a numerate workforce from which to draw.

Although maths would be compulsory, an A-Level in it would not and there may be need for new “innovative” options, he said.

When thinking about what these innovative options could be, it is vital to look at what skills we are trying to teach and assess.

Numeracy is not only about acquiring a set of skills by the age of 18, I would argue.

Just as literacy is not simply the ability to read and write but also a means to civic participation, numeracy is also about developing the knowledge needed to exercise citizenship in a contemporary, data intensive society.

National Numeracy defines numeracy as “the ability to understand and use maths in daily life” including work.

This suggests an applied form of mathematics, requiring less complex knowledge of maths but sufficient understanding to successfully navigate a range of situations including managing finances, using spreadsheets or understanding information presented in charts and graphs.

Data literacy is ill-defined.

It has been used to describe the skills and competencies needed to work in data intensive jobs as ‘data workers’ but also other less data-focused aspects of life which increasingly involve data.

It may be involved in Sunak’s reimagining of numeracy and can be seen as a key competency to be gained by students before leaving school.

In this context, the education system needs to respond to these developments and ensure that young people leave compulsory education with a grounding in the data skills employers need and upon which they will build over the course of their worklife in a ‘datafied’ society.

Sunak’s apparent belief in datafication – suggested by his observation that ‘data is everywhere’ - refers to the importance and status of digital data in contemporary Western societies.

Increasingly, our lives are represented by and understood through data produced by devices such as fitness trackers, online shopping portals or learning apps.

Data, produced in ever larger quantities, has become an essential component of many areas of work.

Consequently, the ability to manipulate, analyse, interpret and present data have become essential employment skills.

Data literacy may be applied to the knowledge needed to enhance understanding of the uses of personal data such as the consequences of sharing it or how it can be used to make lifestyle changes.

It is also essential to understanding how society can be improved through the application of data or how to engage with, and participate in, civic society using digital tools.

In an increasingly datafied society there is a logic to supporting citizens to develop and maintain numeracy skills beyond the age of 16.

Placing numeracy as a central educational objective reflects, not only its value for economic prosperity but also its relationship to participation in civil society.

It will also help guide how and what we assess in those students who would not necessarily choose to do maths to 18.

Read More On This Subject:

GCSE Maths and Numeracy: They don’t equal the same | AQi powered by AQA

The role of assessment in meritocracy | AQi powered by AQA

Who is responsible for Digital Literacy? | AQi powered by AQA

Time to top-up? Rethinking Maths and English after 16 | AQi powered by AQA