AQA - Extended Project Qualification - March 2022

Cages Through the Ages: How Have Concerns for Animal Welfare Impacted on the Regulation of UK Hen Farming for Egg Production?

Contents

| Introduction | 3 - 5 | |

| 1 | Historical Development of Hen Farming for Egg Production in the UK | |

| 1.1 Hens in the 1800s | 6 | |

| 1.2 How the World Wars Affected Poultry as Livestock | 7 - 8 | |

| 1.3 The Introduction of Battery Cages and Farms to the UK | 8 - 10 | |

| 2 | Legal Development of Hen Farming for Egg Production in the UK | |

| 2.1 The First Laws Regarding Battery Farms | 11 - 13 | |

| 2.2 The Abolition of Battery Farms and Introduction of ‘Enriched’ Cages | 13 | |

| 2.3 The Failure of the UK ‘Enriched’ Cages | 13 - 15 | |

| 3 | International Comparison | |

| 3.1 Analysis of Other Countries’ Approaches to Cages and Hen Welfare | ||

| 3.1.1 Switzerland | 16 - 17 | |

| 3.1.2 Sweden | 17 - 18 | |

| 3.1.3 Germany | 18 | |

| 3.1.4 Austria | 18 - 19 | |

| 3.2 The EUs Commitment to Phasing Out Cages for Animals by 2027 | 19 - 20 | |

| 4 | Current Status and Possible Future Developments in the UK | |

| 4.1 Where are We Now? | 21 - 22 | |

| 4.2 The Arguments Against Change | 22 - 24 | |

| 4.3 The Position of the Retail Sector | 24 - 26 | |

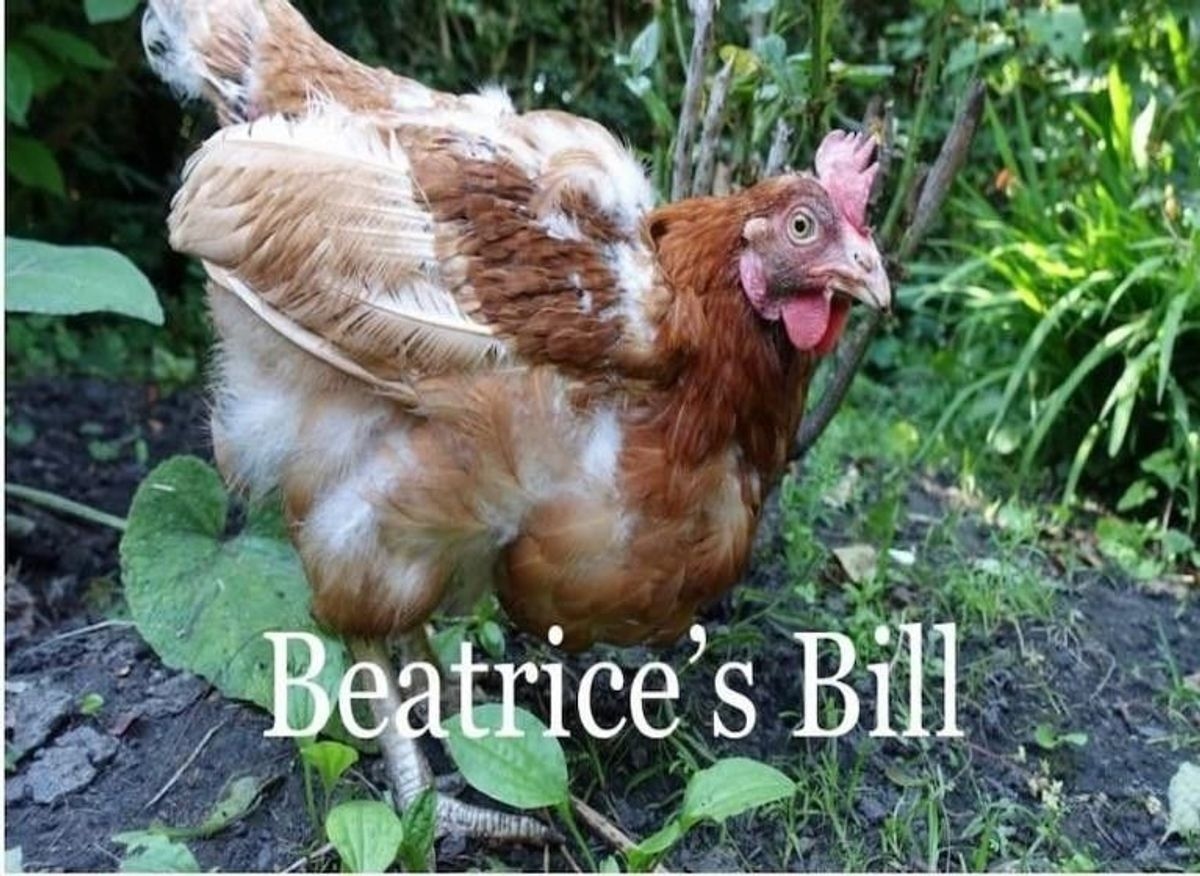

| 4.4 How Beatrice’s Bill Could Affect the Future of Egg Production in the UK | 26 - 28 | |

| 5 | Conclusion | 29 - 31 |

| Reference List | 32 - 39 | |

| Bibliography | 40 - 52 |

Introduction

With 90% of all eggs consumed in the UK being laid by British hens (O’Carroll, 2019), egg production in the UK is big business, so it is understandable why UK Revenue and Customs would want to protect it, however, as a supposed nation of animal lovers, shouldn’t the UK Government protect the hens too? This essay will explore whether it is truly possible to do both.

Egg production in the UK is a highly grossing industry. Based on an industry estimation, 12.9 billion eggs were consumed in the UK in 2020, equating to 35.5 million eggs per day. With an estimated population of 66 million, we each consume 194 eggs per year (British Lion Eggs, 2021).

Whilst some of these figures represent imported shell eggs, the number of imports exceeds exports. In August of 2021, imports exceeded exports by as many as 20,000 cases, showing a UK self- sufficiency of 89% (Department for Environmental Food & Rural Affairs, (DEFRA) 2021). The value of the UK egg industry is worth over £1 billion to the UK economy (Countryside, 2021).

Over recent years, the production output has gradually shifted its balance from caged flocks to free-range, from 27% of all UK eggs produced in 2004 from free- range hens, increasing to 54% in 2008 (British Lion Eggs, 2021). With such demand, it is clear to see that caged hens still produce a significant number of eggs each year.

There is no doubt that many farmers see benefits in caged production. The space required for caged hens is significantly less than free-range hens, the economies of scale and efficiency of production and collection make the caged hen business model difficult to argue against on a financial basis. However, animal welfare has long been a concern to producers, retailers, and ultimately to

consumers. Caged hens suffer through the lack of adequate space and the restriction of natural behaviours including running, flying, wing flapping, and a restriction on the ability to exercise (Hansard, UK Parliament, 2021). The use of cages has been condemned by a number of animal welfare bodies, including the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA),(n.d.a).

This essay will consider how the UK has addressed concerns over the welfare of laying hens historically, how we have compared to other countries and what future plans may be needed to ensure that animal welfare is addressed, whilst maintaining the necessary output to satisfy the consumers’ demands.

The first chapter will detail the historical development of hen farming for egg production in the UK. This chapter will explain the increase in demand for eggs and how farming has changed to meet them.

The second chapter will consider how laws have changed and developed in the UK, the influence of the European Union (EU) and how these changes, alongside public pressure, have impacted farming practices to the present day.

The third chapter will focus on a comparison between the UK and other European countries in their approach to the welfare of laying hens and whether the UK can take guidance or inspiration from other countries with similar demands and demographics.

The final chapter will detail what we can expect for the future of hen farming for laying hens in the UK. It will explore the commitments of retailers due to public pressure and analyse the possible improvements that the introduction of the Hen Caging (Prohibition) Bill (Hansard, UK Parliament, 2021) to parliament may bring.

The conclusion will bring together the ideas explored throughout the essay, consider whether animal welfare has truly been at the forefront of developments in UK poultry farming for egg production and what else might need to be done.

Chapter 1 – Historical Development of Hen Farming for Egg Production in the UK

1.1 Hens in the 1800s

Historically, hen-keeping was a mostly female task. Often a menial duty, managed by farmers wives to earn ‘pocket money’; flocks were small (normally around 200- 400 birds) and fed on farmyard scraps (Godley & Williams, 2007).

In 1842, Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert imported a rare breed of hen from China. These were named Cochins and were regarded as an exotic breed. The Queen was extremely impressed with the large hens and showed them off to her visitors as well as mailing their eggs to her extended royal family across the continent. Andrew Lawler in ‘Why Did the Chicken Cross the World?’ states “every visitor went home to tell tales of the new fowl that were as big as ostriches, and roared like lions, while [they] were gentle as lambs.” (Lawler, cited in National Geographic, 2015a),

This fad became known as “hen-fever” or “The Fancy” and spread to North America. Victorian breeders became obsessed with creating ‘ever fluffier and outlandishly rotund’ birds, in a variety of colours with many of those bloodlines still existing today (National Geographic, 2015b).

Queen Victoria’s Cochins (Chickend.allotment- gardenn.org, 2016)

Some of these breeds had developed an increase in egg-laying and meat capabilities which would become pivotal over the next 100 years. The hobby was, however, extremely expensive, with a pair of cochins valued as high as $700 (National Geographic, 2015b).

Over time, the hens slowly lost their appeal and by 1855, hens had regained their traditional barnyard status. As a result of hen fever however, there were a lot more of these birds than ever before and people began to recognise their value in laying eggs. (National Geographic, 2015a)

1.2 How the World Wars affected Poultry as Livestock

Towards the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century, hens were mainly found in rural gardens to provide meat and eggs for their keepers. By the outbreak of the First World War, on August 4th 1914, Britain was 60% reliant on imports for food supplies and other supplies such as fuel and fertilisers (National Farmers’ Union (NFU), n.d.). However, this spurred development in the poultry sector which enabled the nation to move from seasonal laying to enjoying British eggs all year round (NFU, n.d.). This was achieved through decades of selective breeding which caused severe disabilities such as osteoporosis (Old Time Farm, 2021), which, according to the National Health Service, is a ‘health condition that weakens bones, making them fragile and more likely to break’ (NHS, 2019).

Before World War 2, Britain’s poultry flock numbered over 50 million and was reared for their egg production, but with the onset of the war, the poultry population rapidly declined as a result of the government prioritising grain for people, not intensive livestock (Farmers Weekly, 2014).

At this time, a family could register to surrender a part of their egg ration in exchange for poultry feed mash coupons (BBC, 2014). On average, six birds were kept by a household, however, the poultry mash ration was inadequate to feed the number of birds registered by an owner. Additionally, it was the poultry keeper’s responsibility to acquire enough food for their poultry, not the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries to provide it.

Supplies were hard to obtain, leading to poor quality produce. However, government-sponsored leaflets containing advice on every aspect of poultry keeping were widely available, regarding feeding, disease control, housing, and general management.

The government encouraged domestic poultry keepers to buy their pullets (young hens) from registered breeders which were allowed special high-quality feed rations so that they could produce healthy laying stock.

This was viewed as an important alternative to domestic back- garden keepers breeding their own from their laying stock which had been fed on low-quality rations, or meagre amounts of feed, resulting in birds with substandard laying capabilities (BBC, 2014).

This compromise in hen-welfare was a consequence of necessity, when desperate times, call for desperate measures, and could be indicative of how the mis-treatment of animals was made acceptable.

1.3 The Introduction of Battery Cages and Farms to the UK

Battery cages derive their name from an artillery battery where units are arranged in rows and columns. An early reference to battery farming was made by Milton Arndt in 1931 and his revised book in 1932 (Arndt, 1932). Arndt made the benefits of battery farming clear, describing how his own trials produced a much favourable laying rate of caged hens when compared to those kept in barns.

Arndt also described how the prevention of disease was easier, explaining the necessity of forced sneezing and coughing together with increased heat. It was also easier to monitor the efficiency of individual hens and their laying patterns (Arndt, 1932).

Despite this, battery cages did not make an immediate impact in the UK.

After the Second World War, livestock grain rationing did not end until 1953, however, the UK government quickly recognised that in order to meet their aim of making the UK more self-sufficient, food production must increase sharply, otherwise the country may find itself reliant on imports to the same extent as before the war.

This need saw the arrival of ‘factory farming’, a rigorous agricultural system whereby productivity and profit were the primary factors. Battery cages were soon at the forefront of ‘factory farming’.

Designed to improve hygiene standards and curb the spread of infectious diseases, the early models of battery cages were promising; housing only one bird each and being made bigger than those of more modern times (Animal Aid, 2016).

The 1950s saw battery cages evolve rapidly to house around 5 laying hens each, these were stacked on top of one another; often reaching six tiers in height. And, as demand for eggs grew, farmers began to use mechanised systems to control access to food and water and use artificial lighting to simulate longer daylight hours, which, coupled with medication and selective breeding techniques, allowed farmers to manipulate their hens into producing more and consuming less (Animal Aid, 2016).

Feeding typically consisted of dry mash, but a new rail system was later introduced giving each hen only about ten minutes of feeding time (Farmers Weekly, 2014), cutting costs whilst reducing waste, which was better for business, but not necessarily for the hens.

Fortunately, these mechanised developments included better manure clearing systems, ranging from tyre scrapers on ropes, to dropping boards and continuous rolls of paper, thus improving hygiene standards.

However, over time, a lack of legal requirements allowed for commerce to take advantage of this increase in productivity to make bigger profits. The number of birds per cage increased and the amount of space per bird decreased, thus began the failure of battery cages. More and more battery farms appeared, and rows of cages continued to be stacked several tiers high for each barn to hold up to 30,000 birds (Animal Aid, 2016).

Prior to the 2012 ban, standard battery cages typically held four or five hens, depending on its size, with each hen having 550cm² of space (which is less than the size of an A4 sheet of paper at 623cm²) (RSPCA, 2005). In the UK, some battery cages held up to ten hens, whilst in other countries such as India and the USA, even more were found in cages of the same size (Compassion in World Farming (CIWF), 2012).

Concerned with high-stress witnessed in caged hens, Bulmer and Gil (2008), compared the levels of corticosterone (a hormone produced to regulate stress- responses) which were found in eggs laid in different farming systems, and concluded; battery hens suffered chronic stress; with free-range being the least affected; and barn hens exhibiting intermediate levels, providing compelling evidence in the debate against battery farms.

Chapter 2 – Legal Development of Hen Farming for Egg Production in the UK

2.1 The First Laws Regarding Battery Farms

The Council of Europe’s 1976 convention on the protection of animals kept for farming purposes set out basic standards for animals kept in intensive farming systems. Support across the EU varied. Appleby describes stronger support from the north of Europe which had an average of 6% of citizens employed in agriculture, compared to Ireland and southern Europe, which saw around 21% of its population involved in agriculture.

Whilst there may have been other factors in the divide, there was a clear difference in the speed in which European countries approved the convention (Appleby, 2003a).

Between 1970 and 1990, there had been a surge in work on alternative housing systems for commercial laying hens primarily focusing on improving animal welfare. As a result of this, some producers kept hens in non-cage systems, covering higher costs with higher selling prices.

Unfortunately, non-cage systems were not regulated to the same extent, and due to a lack of specifications, some problems occurred, for example, some eggs sold as free-range could only ‘range’ in a barn, which was not necessarily what the public was expecting from their more expensive purchase.

This was still better than a caged alternative as far as animal welfare was concerned, however, consumers paying higher prices for their eggs were unaware of this loophole.

This led to the introduction of a labeling system by the EU in 1985. These four labels were ‘Free-range’, ‘Semi-intensive’, ‘Deep-litter’, and ‘Perchery’ (or ‘Barn’) and they had to meet the requirements published by the Commission of the European

Communities 1985. The criteria for Free-range was that a system must provide ‘continuous daytime access to ground mainly covered by vegetation [and the] maximum stocking density was 1,000 hens/hectare’ (Appleby, 2003a). For a Semi- intensive label ‘continuous daytime access to ground mainly covered with vegetation [and] maximum stocking density 4,000 hens/hectare’ are required (Appleby, 2003a).

Deep-litter systems demand ‘a third of floor covered with litter, part floor for droppings collection [with a] maximum stocking density 7 hens/m²’ (Appleby, 2003a). Whereas Percherys or Barns stipulate ‘perches, 15 cm for each hen [and] a maximum stocking density of 25 hens/m²’ (Appleby, 2003a).

In 1987, due to the implementation of a European Community directive setting out minimum welfare standards, the UK introduced its first law regarding a minimum size for battery cages. The Welfare of Battery Hens Regulations 1987 made it a criminal offence to fail to meet the designated area for each hen.

Where only one hen was kept in a cage, a minimum area of 1000cm² was prescribed. This decreased to 750cm² where two hens were caged; 550cm² for three caged hens; and 450cm² for four. That space was also required to be used without restriction, so that no encroachment was made into the space, except for the non-waste deflection plate (otherwise known as the egg guard).

In 1989, researchers Dawkins and Hardie reported that brown hens, just standing still, took up to 475cm², and when turning around, 1,272cm². However, in 1992, the European Commission’s draft for a new directive only recommended that cages should provide 800cm² per hen (Appleby, 2003b), meaning that although this figure was above that required by a standing hen, as recognised by Dawkins and Hardie in 1989, and was greater than the 550cm² provision that the RSPCA reported in 2005, this 1992 EU measure still fell short of the Dawkins and Hardie (1989) findings for a hen to turn around, so clearly, more needed to be done.

Nevertheless, this was a significant step. Prior to this, around half of the hens in Europe were given less than 450cm² each. There were calls for more space for these hens, and it was quickly recognised that many consumers would pay more for non-cage eggs.

2.2 The Abolition of Battery Farms and Introduction of ‘Enriched’ Cages

In 1999, as a result of a thirty-year scientific study by the European Scientific Veterinary Committee, the EU decided to ban ‘barren’ battery cages as being ‘unacceptably cruel’ (Animals Australia, 2012). Taking three years to enforce, this ban came into being on January 1st 2012, for the industry to prepare for the new regulations without unnecessary costs incurred through time constraints.

Therefore, being part of the EU at that time, battery cages have been banned in the UK since 2012. However, this did not mean a ban on caged hens. Instead, this led to a surge in popularity for the alternative ‘enriched’ cages in the UK. According to Stevenson (2012), the 2002 regulations dictate that each ‘enriched’ cage must provide each hen with a minimum of 600cm² of usable floor space, being at least 45cm in height, which was 7cm taller than its predecessor (RSPCA, 2005). Although an improvement, these regulations still fall short of the 1,272cm² floorspace that Dawkins and Hardie (1989) identified as being needed for a hen to turn around, thus lending credible evidence to show how ‘enriched’ cages are not a suitable alternative to battery cages.

2.3 The Failure of the UK ‘Enriched’ Cages

According to Animal Aid (2016), ‘enriched’ cages currently only provide 50cm² more useable space than their condemned predecessors – battery cages. Moreover, in common with battery cages, ‘enriched’ cages are stacked on top of each other, row upon row, and provide limited facilities for nesting, perching on scratching (RSPCA, 2005).

However, the increased size of ‘Enriched Colony Cages’ has come with an increase in the number of hens per cage. The original ‘enriched’ cages held ten hens on average, but the more recent systems known as ‘Colony’ cages can hold 60-80 hens per cage (Animal Aid, 2016) and have now become the most common caged system in the UK.

‘Enriched’ cages are not ‘barren’ as battery cages were. For example, one improvement of ‘enriched’ cages over battery cages is the addition of perching facilities.

A perch provides respite from standing on the sloped, wire, cage flooring; designed to collect the eggs, and according to Olsson & Keeling (2002), encourages the natural behaviour performed by flocks in the wild to reduce the risk of predation and conserve heat.

Unfortunately, the introduction of these essential facilities has also exacerbated multiple health problems in hens. The RSPCA (2005) reported that the positioning of perches can reduce accessibility and useable space. Additionally, Appleby, Duncan & Hughes (1991), claim that some hens laid eggs from the perches, resulting in cracked eggs.

Moreover, Lay Jr, Fulton, Hester, Karcher, Kjaer, Mench, Mullens, Newberry, Nicol, O’Sullivan, & Porter (2011) observed a build-up of faeces under the perches due to the perch position and the habit of hens which can be difficult to clear away and lead to health problems such as bumblefoot; a type of infection causing swelling, redness, and black or brown scabs, and which, if left untreated, claims The Chicken Chick (n.d.), can be fatal, as the infection can spread to other tissues and bones.

Bumblefoot (British Hen Welfare Trust, n.d)

Other negative side-effects reported in hens in ‘enriched’ cages are deformed keel bones. Keel bones are ‘the prominent ridge on the sternum of flighted birds to which the powerful wing muscles attach’ (Universities Federation for Animal Welfare, n.d.).

It has been suggested by the RSPCA (2005), that this deformity could be due to the inappropriate shape or position of perches, alternatively, they claim it could be due to hens perching for prolonged periods of time since there is inadequate room available for them to move around and perform other natural activities.

More recent research by Habig, Henning, Baulain, Jansen, Scholz and Weigend, confirmed bone mineral density, body growth rate and laying performance are all negative side-effects of keel bone damage caused by cages (2021). Therefore, the adoption of ‘enriched’ cages, which aimed to address the welfare argument and improve the quality of life of laying hens, still appear unsuitable. They fail to provide a satisfactory solution to the welfare and commercial balance, meaning the need is still ongoing.

Hens in an 'enriched' cate (The Scottish Farmer, 2021)

Chapter 3 – International Comparison

3.1 Analysis of Other Countries’ Approaches to Cages and Hen Welfare

- Switzerland

Hen welfare was not just an isolated issue for the UK to contend with. Public pressure in other countries across the world also prompted action for various governments and overseas producers. In 1981, Switzerland introduced an animal welfare related pre-testing procedure for large-scale laying, hen-housing systems (RSPCA, 2005).

This essentially initiated a ten-year phase-out of conventional battery cages, ending in 1991. After this, many different modified cages were developed and tested. However, observations by the RSPCA (2005), revealed that these cages exacerbated many welfare issues such as: hens being unable to differentiate between nesting and activity areas; pacing along cage boundaries; dust bathing not being facilitated; injurious feather pecking; and high mortality rates (mainly due to cannibalism). Due to these results, the Federal Veterinary Office denied permission for the construction and distribution of these modified cages for commercial egg production (RSPCA, 2005).

Additionally, the ban of battery cages in Switzerland was coupled with a ban in beak trimming, in doing this, Switzerland became the first country to address the barbaric practice. Beak trimming is used as a preventive measure to avoid cannibalism and is carried out using an infra-red beam to remove the sharp tip of a hen’s beak, which according to British Hen Welfare Trust (n.d.b), takes seconds and is carried out when the birds are at chick stage.

However, CIWF (n.d.), claim the section which isremoved is much more than just the sharp tip and contains fine nerves, leading to the conclusion that the procedure is far from painless, and could be a practice to be addressed in the UK.

It has been questioned whether individual hen health has improved by allowing these cage-free hens to roam free, due to increased exposure to the environment with natural predators and disease.

However, Studer (2001) found that since 1992, cases of salmonellosis and Newcastle Disease (NCD) (general diseases affecting hen health), have decreased in Switzerland, making Switzerland a prime example for the UK to learn from in these areas.

3.1.2 Sweden

In 1988, Sweden passed an Animal Welfare Act requiring 600cm² per bird in all new cages. It also mandated that by 1994 all cages must be fitted with a claw shortening system and a perch (Appleby, 2003b). The Act also said that from 1999, hens should not be kept in cages.

In addition to this complete ban, conditions were imposed on alternative methods of farming. It ruled that alternatives must not impair mental health of the animals and that there was to be no increased medication as a result of the alternative systems, as well as no beak trimming and no impaired working environment (Appleby, 2003a).

Unfortunately, in 1997, it was decided that the conditions could not be met, as the ban would cause a predicted 60% rise in egg imports. Hence, the ban was deferred. Instead, it was decided that all cages must be ‘enriched’ cages, which were introduced commercially in Sweden from 1998. The ban on beak trimming was not withdrawn, but interestingly, Sweden subsequently reported no problems of cannibalism (Appleby, 2003b).

Therefore, due to Sweden’s failure to implement such stringent conditions, this could be an indicator to the UK to allow manageable deadlines for the industry to adopt any new regulations, if they are to succeed.

3.1.3 Germany

In 2005, Germany was considering a ban on conventional cages to be introduced by 2007 and for no cage systems to be utilised by 2012 (RSPCA, 2005). However, this was deferred in light of the EU Directive. Nevertheless, Germany has now made a commitment to going cage-free by 2025, meaning in three years’ time, all of Germany’s commercial laying hens will be in barn or free-range systems (CIWF, 2015). Seemingly, the country is on track to meet this target with huge decline in the percentage of hens in cages, dropping from 87% in 2000 to 10% in 2015 and 6% in 2020 (Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2021).

The Albert Schweitzer Foundation describes itself as ‘advocates for animal rights’, focussing on farmed animals. It proudly states that its ‘cage-free work in Germany is mostly done’. Interestingly, the Foundation is now turning its attention to tackling the issue of beak-trimming (Albert Schweitzer Foundation, 2021). This shows that a cage free system in a leading European country is a feasible option and one the UK could adopt.

3.1.4 Austria

Austria took a similar stance to Germany and announced that after January 1st 2005, no new cages would be built. Whilst conventional battery cages were able to be used these were to face a complete ban by 2009. ‘Enriched’ cages that were in production prior to 2005 could, however, continue to operate for 15 years from the date they were built (RSPCA, 2005). Nevertheless, the ban prevented the manufacture of new ‘enriched’ cages and led to all cages being phased out by 2020 (CIWF, n.d.).

Recognising hen welfare extended to more than just housing, in 2000, a scheme was introduced to phase out beak trimming. Though beak trimming was not made illegal, it was made more expensive with the intention that a fund could be created to provide compensation for any farmers who lost hens through cannibalism as a result of the lack of beak trimming.

Those who agreed to be part of the scheme were required to pay a certification fee of €14.5 per hen, increasing annually from its commencement in 2002 (CIWF, n.d.).

Therefore, Austria’s approach provided commercial incentives to farmers, seeking agreement and buy-in, as opposed to the enforcement of an outright ban. Whilst this only related to beak trimming, similar incentives could arguably be extended to wider welfare issues in the UK and beyond.

3.2 The EU’s Commitment to Phasing Out Cages for Animals by 2027

As previously mentioned, the EU banned conventional (battery) cages in 2012. Resulting in a vast increase in popularity of ‘enriched’ cages for the laying sector. However, largely due to public pressure, 2021 saw the EU declare its intention to introduce legislation to phase out cages completely by 2027 (CIWF, 2021).

The legislation will be proposed formally by 2023, with the changes being gradually phased in by 2027 (BBC, 2021). As with many legislative interventions, this move was prompted by public pressure, notably following a petition demanding an end to the caged system obtaining more than 1.4 million names (BBC, 2021).

Stella Kyriakides, the European Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, supported this and responded to the public mood by ‘tweeting’: 'This is a historic day for animal welfare [in the EU]. 1.4 million united [voices] have asked us to #EndTheCageAge. I am pleased to announce that by the end of 2023, we will make a proposal to phase out the use of cages for millions of farm animals. This #ECI is EU democracy in action. (Kyriakides, 2021).

Stella Kyriakides (BBC, 2021)

However, as the UK is no longer a part of the European Union, there is no obligation to adhere to the EU directive to phase out cages by 2027 and therefore is not bound to commit to this ruling.

Chapter 4 – Current Status and Possible Future Developments in the UK

4.1 Where are we now?

The UK enforced the European ban on battery cages in January 2012 (DEFRA, 2011). This meant the industry became reliant on ‘enriched’ cages which, as stated, offer approximately 50cm² more useable space per hen than conventional cages (RSPCA, 2005).

These ‘enriched’ cages stack on top of one another in long rows much like the banned battery cages and some cages house up to 60 hens, sometimes more. The criticisms of caged systems considered in Chapter 2 show that the UK still has no suitable enforced alternative to conventional cages.

Following the European Commission’s Scientific Veterinary Committee’s findings of battery cages being ‘cruel’ in 1996, the Council of the European Union banned their use across the EU in 1999, and replaced them with larger, supposed ‘enriched’ cages.

However, it took a further three years to end the installation of any new battery cages, with another ten-year window to phase them out altogether, which according to Animal Aid (2016), ‘gave the egg industry a generous 13 years to change from one type of cage to another.’

The then Animal Welfare Minister, Elliot Morley announced in 2002 ‘I am not convinced ‘enriched’ cages have any real advantages’ and called for a public enquiry on whether all cages should be banned (The Guardian, 2002).

In response, the NFU launched a campaign against an outright ban, arguing there was yet to be conclusive evidence produced on the disadvantages of cages on hen welfare and claiming that a ban on ‘enriched’ cages would ‘devastate the [UK poultry] industry’ (Daelnet, 2002).

During the enquiry period, DEFRA paid for research into cages and the NFU accused Mr Morley of seeming to be ‘pressing for an immediate decision… [appearing to] want to base this consultation on emotion, not fact’ (NFU, 2002).

Thus, providing evidence of the level of resistance from the industry to conform to these animal-welfare driven improvements when profits are at stake.

Following the three-month consultation, an outright ban on ‘enriched’ cages was ruled-out on ‘insufficient grounds’ leading Elliot Morley to claim it would be best decided through the EU in 2005.

In response, the charity Animal Aid accused Elliot Morley of ‘passing the buck’ which, by deferring the decision, bought the caged-hen, egg production industry another three years to continue with their current practices. (Animal Aid, 2016)

At present, the UK is still at least three years away from phasing out all caged-hen eggs from supermarkets and food production as per the EU directive. However, as previously stated, as the UK is no longer a part of the European Union, there is no obligation to adhere to the EU directive to phase out cages in line with the EU.

4.2 The Arguments Against Change

Despite the Conservative Animal Welfare Foundation (CAWF)’s (2022) research claiming, ‘cages severely damage the wellbeing of hens, restricting their movement and frustrating their ability to perform innate behaviours like wing flapping, stretching, body shaking, tail wagging, foraging, dustbathing, perching and nesting’, the public consultation would have sought evidence at that time to negate concerns over the welfare of hens in ‘enriched’ cages. Whilst produced later, evidence shows that ‘enriched’ cages do have some merit.

Jansson (2018) (like Studer, 2001), suggests that caged hens are at less-risk to micro-organisms and some parasites than free-range hens which are more exposed to these risks, including Avian Influenza (Bird Flu). This is a collection of viruses which are highly contagious in birds and has resulted in the UK government’s chief veterinary officer Christine Middlemiss to legislate that captive birds must be kept indoors to prevent contact with wild, migrating birds which could carry the illness by introducing Avian Influenza Protection Zones (AIPZs) (The Independent, 2020a).

This is where hens in caged (and barn-systems) have an advantage, as they not only provide protection from predators like foxes or birds of prey, but they can also protect against these environmental pathogens.

Although it is believed that humans cannot catch most strains of the virus, they pose a risk of spreading this highly transmissible disease (Hancock, 2020) and can transfer it via clothing and during transportation. Therefore, strict biosecurity measures have also been introduced to combat this, which, unfortunately would have an added cost-factor to the industry.

The requirement to keep hens indoors to protect from Bird Flu has led the RSPCA to warn that the sudden change in environment, could cause stress in free-range birds who are not used to being kept indoors, and this could make them susceptible to disease (Dalton, 2020).

Some other benefits of ‘enriched’ cages are that it is easier for keepers to recognise and treat ailing hens due to them being housed in smaller groups (Australian Eggs, 2022).

Furthermore, there is no nutritional difference between cage-laid, barn-laid or free-range eggs, and Australian Eggs (2021) also claims that cage-eggs have a lower carbon footprint than free-range eggs, making them better for the environment.

Additionally, even though free-range systems are praised, and seen as a perfect alternative for cages in the laying sector, questions have been raised as to whether this is the case.

Animal Welfare Professor Christine Nicol from Bristol University stated that ‘although free-range farms had potential to offer birds a better quality of life than their caged counterparts, many had poor welfare standards’ and that caged- hens were ‘less likely to break bones or injure each other through pecking, suffered less stress and had lower mortality rates.’ (McDermott, 2013).

Furthermore, Australian Eggs (2019) argues that ‘one system is not better than the other, the welfare of the hens is more reliant on the management of the farm, than the system.’

4.3 The Position of the Retail Sector

2019 saw the processing and foodservice sector make up 41% of the egg market with the other 59% coming from retail (Farmers Weekly, 2021). Since large retailers make up such a significant percentage of the market, a clear commitment to selling eggs from cage-free birds would force producers to also commit to these developments.

According to CIWF (2020), 77% of the UK public would like to see a complete ban on cages. UK retailers are now taking a similar view, with Sainsbury’s becoming the first UK supermarket to go cage-free in 2008, even before the EU ban on battery cages (Poultry World, 2008).

Whilst many other supermarkets are doing the same, not all are taking this approach, possibly to keep their prices low and keep their existing customers happy. Some are introducing a long phase-out period for caged eggs.

Waitrose has only sold cage-free eggs, including as ingredients, since 2008 (CAWF, 2022). It could be argued that this was mainly made possible due to Waitrose’s customer demographic being older with higher disposable income, more willing to pay for quality rather than quantity.

This is in contrast to the budget supermarket’s demographic whose customers demand lower priced goods and more value for money. This may explain why some supermarkets did not commit to going cage-free until 2016 and only then promising to end the sale of eggs from caged hens by 2025. These include, Aldi, Tesco (White, 2016 a ; 2016 b), Asda (Webster, 2016), Morrisons, Iceland (Shepherd, 2016), Booker, Nisa, and Spar (Hawthorne, 2016).

Seemingly, food production companies and food service providers have also slowly entered the agreement. Compass Group, the world’s biggest food service provider, worked out a nine-year plan with Compassion in World Farming to going cage-free by 2025, after bowing to pressure from a petition through ShareAction (Davies, 2016).

In contrast, food production company Nestlé are already there, stating:

'Farm animals deserve decent welfare standards. Nestlé supports a phasing out of caged systems for all egg laying hens, building on industry efforts to date. We’re proud to source 100 per cent cage free eggs for all our food products in the UK'.” (Sussex World, 2021)

It seems this delay in implementation has allowed some companies to experience the best of both worlds while the changeover takes place. Noble Foods who owns The Happy Egg Company is a market-leader in promoting the lifestyle and welfare of their free-range hens as being ‘the cornerstone of everything we do’. However, the company also keeps 4.3 million hens in ‘enriched’ cages under their Big & Fresh brand (Webster, 2017).

The Humane League accuse Noble Foods of hypocrisy by spending £100 million on the installation of new cage systems prior to the 2012 deadline. This would have been unknowingly financed, at least partly, by its Happy Egg customers, despite no clear commitment to going cage free.

4.4 How Beatrice’s Bill Could Affect the Future of Egg Production in the UK

On 23rd June 2016, the UK held a referendum to determine whether it should remain a member of the European Union. 51.89% of voters voted to leave. The enactment of The European Union (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 said the UK would formally leave the EU on 31st January 2020. Brexit, as it is commonly known, has resulted in the UK government reviewing existing laws and whilst there is no suggestion that the EU ban on battery cages will be reversed, it does mean that the UK is not bound by the same EU commitment to phase out all cages by 2027.

The UK is therefore free to legislate as it sees fit. However, with pressing matters, in the form of continuing Brexit issues, the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, the war in Ukraine and a pending cost of living crisis, there is often little parliamentary time or interest for less urgent matters.

The Hen Caging (prohibition) Bill Volume 701 was introduced by Henry Smith, the Conservative MP for Crowley under the Parliamentary Ten-Minute Rule. Its first reading was debated on 22nd September 2021.

The Bill proposes to completely ban cages for hens and is informally known as ‘Beatrice’s Bill’ named after an adopted rescue hen found in an unfortunately common, extremely tatty and unhealthy state.

Mr Smith introduced the bill by explaining that: ‘The people of Britain are some of the most caring and compassionate people in the world. We are a nation of people who care about justice, about each other and, of course, about animals.’ (Hansard, UK Parliament, 2021).

His comments in this regard show the public view, although the petition on Change.org which was recognised by Mr Smith (CAWF, 2021), had, at the 4th January 2022, only collected 90,652 signatures.

The petition was started by Mia Fernyhough, who describes herself as an ‘animal welfare specialist and hen rescuer’. Ms Fernyhough describes her rescue of Beatrice and details her rehoming and progress, leading to the Bill being known as ‘Beatrice’s Bill’.

Whilst this may seem a significant number, it has not yet reached the 150,000 signatures that are needed to make the petition one of the ‘top signed on Change.org’ and has achieved less than half of the 279,000 signatures that the petition ‘End the sale of eggs from caged hens in Tesco’ managed to achieve (Change.org, 2016) and less than 20% of those signing the petition to stop McDonalds handing out plastic toys with children’s’ ‘happy meals’ (Change.org, 2019).

Mr Smith explained that despite the ban of battery cages in 2012, ‘enriched’ cages were detrimental to hens’ wellbeing. He continued: ‘Countries such as Austria, Switzerland and Germany have banned cages for hens.

On 8 June 2021, Nevada became the ninth US state to ban the use of cages for laying hens, and just two weeks ago the EU committed to phasing out cages for animals by 2027. The Bill is therefore key to the UK’s claiming its place at the forefront of animal welfare standards and ending the unnecessary suffering of millions of hens like Beatrice.’ (Hansard, UK Parliament, 2021)

The Bill is due to have its second reading on Friday 28th March 2022 (UK Parliament, Parliamentary Bills 2022). The second reading is the first opportunity for the Bill to be debated in Parliament and for MPs to consider the main principles proposed by the Bill. This date will determine whether the Bill will progress any further.

If it is successful in its second reading, the Bill will then pass to the ‘Committee Stage’, where the proposals are looked at in more detail, evidence is given by experts and amendments proposed as a result of these considerations. If the Bill is successful through the ‘Committee Stage’ the Bill will return to the House of Commons for further debate and review.

Beatrice (CAWF, 2021)

With the UK no longer being bound by the EU promise to ban cages and no other current government proposals, this may be the only opportunity to bring an end to cages this decade.

Conclusion

When considering the points raised throughout this essay concerning whether animal welfare has truly been at the forefront of developments in commercial hen farming for egg production in the UK, it appears the main issue that has impacted on decisions, has been whether it is possible to create a viable business model which can operate successfully within the parameters of animal welfare-conscious regulations.

As shown in chapter one, the use of battery cages prior to the introduction of these animal welfare-conscious regulations focused solely on profit and ease for farmers and this attitude has seemingly changed insubstantially through the years as explored in chapter 4 through the campaign launched by the NFU to oppose the proposed ban of cages in 2002. It seems that whenever proposals are put forward, time delays ensue to allow filtration throughout the industry, and provide a buffer to absorb financial instability throughout the transitional stage, this in turn, allows the undesirable practice to continue, which could be argued, although is a driver for change, goes against animal welfare as being at its core.

Despite these problems, other countries have managed to advance beyond the UK’s position as far as cage free egg production and indeed hen welfare is concerned.

Switzerland have manged to ban cages and beak trimming completely. Sweden still permits ‘enriched’ cages, following a reversal of it’s proposed ban, but have outlawed beak trimming. Austria have taken a more innovative approach to beak trimming, providing commercial incentives to farmers, discouraging the practice, with cages being phased out at the start of the decade. Germany have committed to cage-free production by 2025 but have yet to address beak trimming.

Whilst cages can be said to have a benefit, the evidence is such that they impact negatively on hen welfare. It is disappointing therefore, that the UK had failed to address the problem and take inspiration from the success, or clear commitments of some of our European neighbours.

Clearly, the UK government still has the desire to maintain the UK’s stronghold on the self-sufficient nature of the egg production business by appeasing the industry with delays and deferrals (like that of Elliot Morley) and long deadlines incurred through ‘phasing-in’ (as in the EU). It is also clear that due to the issue being raised through petitions, on social media and in the press that there is some public pressure to move to cage free production and this is shown in the attitudes and actions of retailers.

However, free-range eggs are more expensive and many supermarkets wish to continue to cater for all customers, providing a low-price alternative when they can, by offering eggs from caged hens. Whilst supermarkets are able to continue to offer this choice to consumers and while there is a demand from sections of the public, it is unlikely that practices will change quickly.

It appears that early in battery cages history, legal loopholes and lack of regulations allowed for the exploitation of the battery cage system by the egg production industry, which in turn, allowed the industry to lose sight of the welfare of laying hens.

Seemingly, the time taken for the industry to reach these lows is now proving an equal time-lapse when attempting to rectify this oversight – as the industry seems slow to release its grip on its profit margin, obtained through this continued oversight in regulations.

Therefore, even though the UK is seen to be a nation of animal lovers, this is not reflected in this essay’s findings. This is arguably due to the profits available to farmers, the revenue for retailers and the bureaucracy involved in implementing new laws. It is clear that more can be done to improve animal welfare; and hen welfare in particular.

The potential for Beatrice’s Bill to become law is an exciting prospect for those committed to animal welfare, but many such Bills have failed at some point along their progression to becoming law. However, it is clear that in the absence of the binding nature of EU membership, this is the best chance that the UK has of banning caged hens completely.

Dedicated to my rescue hens: Leia, Padmé and Rey.

Reference List

Albert Schweitzer Foundation. (2021, April 12). Cages for Laying Hens Below 6% in Germany. Retrieved from: https://albertschweitzerfoundation.org/news/cages-for- laying-hens-below-6-in-germany

Animal Aid. (2016). The Battle of the Battery Cage. Retrieved from: https://www.animalaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/BatteryCage.pdf

Animals Australia. (2012, March 27). Battery cages banned in Europe. Retrieved from: https://animalsaustralia.org/latest-news/eu-bans-battery-hen-cages/

Appleby, M. (2003a). The EU Ban on Battery Cages: History and Prospects. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 6(2), pp.159-174. Retrieved from: https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/archive/assets/pdfs/hsp/soa_ii_cha p11.pdf

Appleby, M. (2003b). The European Union Ban on Conventional Cages for Laying Hens: History and Prospects. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 6(2), pp.103-121. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12909526/

Appleby, M., Duncan, E. T., & Hughes, B. O. (1991). Effect of perches in laying cages on welfare and production of hens. British Poultry Science, 33, 25-35. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00071669208417441

Arndt, M. (1932). Battery brooding; a complete exposition of the important facts concerning the successful operation and handling of the various types of battery brooders. (2nd ed.) Retrieved from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924003197419&view=1up&seq=318

Australian Eggs. (2019, April). Effects of phasing out cage farming in Europe. Retrieved from: https://www.australianeggs.org.au/assets/dms-documents/Effects-of- phasing-out-cage-farming-in-Europe.pdf

Australian Eggs. (2021, 27 January). Assessing the carbon footprint of the egg industry. Retrieved from: https://www.australianeggs.org.au/what-we-do/leading- research/assessing-the-carbon-footprint-of-the-egg-industry

Australian Eggs. (2022). Egg farming systems: welfare science review. Retrieved from: https://www.australianeggs.org.au/what-we-do-/leading-research/egg-farming- systems-welfare-science-review

BBC. (2014, October 15). 1939-45 The War Years by F. G. Imm. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/02/a8435702.shtml

BBC. (2021, June 30). Caged animal farming: EU aims to end practice by 2027. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-57668658

BHWT. (British Hen Welfare Trust). (n.d.a). Bumblefoot. Retrieved from: https://www.bhwt.org.uk/hen-health/health-problems/bumblefoot/

BHWT. (British Hen Welfare Trust). (n.d.b). Beak Trimming – Mutilation or a Necessity? Retrieved from: https://www.bhwt.org.uk/beak-trimming/

British Lion Eggs. (2021). Industry Data. Retrieved from: https://www.egginfo.co.uk/egg-facts-and-figures/industry-information/data

Bulmer, E. & Gil, D. (2008). Chronic Stress in Battery Hens: Measuring Corticosterone in Laying Hens. International Journal of Poultry Science, 7(9), 880- 883, 2008. ISSN 1682-8356

CAWF. (Conservative Animal Welfare Foundation). (2021, September 23). Hen Caging (Prohibition) Bill- Beatrice’s Bill. Retrieved from: https://www.conservativeanimalwelfarefoundation.org/end-cages-for-egg-laying- birds/cawf-patron-henry-smith-mp-brought-a-10-min-rule-bill-before-the-house-of- commons-to-end-cages-for-egg-laying-birds-the-bill-passed-its-first-reading-the- second-reading-will-be-held-on-oct-22nd-2/

CAWF. (Conservative Animal Welfare Foundation). (2022, February 1). Waitrose Supports Ending Cages for Laying Hens. Retrieved from: https://www.conservativeanimalwelfarefoundation.org/end-cages-for-egg-laying- birds/enry-smith-mp-led-the-hen-caging-prohibition-bill-known-as-beatrices-bill-after- the-rescue-hen-at-the-centre-of-a-campaign-coordinated-by-conservative-animal- welfare-fou/

Change.org. (2016). End the sales of eggs from caged hens in Tesco. Retrieved from: https://www.change.org/p/tesco-ban-the-sales-of-eggs-from-caged-and-barn- kept-hens

Change.org. (2019). Save the environment - Stop giving plastic toys with fast food kids meals. Retrieved from: https://www.change.org/p/burger-king-mcd-s-save-the- environment-stop-giving-plastic-toys-with-fast-food-kids-meals

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2012, March 1). The Life of: Laying hens. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/media/5235024/The-life-of-laying-hens.pdf

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2015, November 5). “AUF WIEDERSEHEN” CAGES. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/news/2015/11/auf-wiedersehen-cages

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2020, December 9). 88% OF UK PUBLIC THINK CAGES ARE CRUEL. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/news/2020/12/88-of-uk-public-think-cages-are-cruel

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2021, June 30). EU ANNOUNCES HISTORIC CAGE BAN. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/news/2021/06/eu- announces-historic-cage-ban

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (n.d.). LAYING HEN CASE STUDY AUSTRIA 1. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/media/3818841/laying-hen- case-study-austria.pdf

Countryside. (2021, February 18). Find out about the British egg sector. Retrieved from: https://www.countrysideonline.co.uk/food-and-farming/feeding-the-nation/eggs/

Daelnet. (2002, June 26). NFU wants “informed debate” on battery hens. Retrieved from: http://www.daelnet.co.uk/countrynews/archive/2002/country_news_26062002.cfm

Dalton, J. (2020, December 10). Bird flu: Chickens and hens must be kept indoors – but their meat and eggs may still be labelled ‘free-range’ - Experts warn stress of being cooped up may make creatures more vulnerable to viruses. The Independent. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/bird-flu-poultry- chicken-indoors-rspca-b1766540.html

Davies, J. (2016). Bird flu and consumer pressure: a global picture. 2016, Poultry World.

DEFRA. (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs). (2011). UK unites to stamp out battery cages. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk- unites-to-stamp-out-battery-cages

DEFRA. (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs). (2021). National statistics, Quarterly UK statistics about eggs - statistics notice (data to September 2021). Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/egg- statistics/quarterly-uk-statistics-about-eggs-statistics-notice-data-to-june- 2021#about-these-statistics

Farmers Weekly. (2014, April 11). Poultry production through the ages. Retrieved from: https://www.fwi.co.uk/livestock/poultry/poultry-production-through-the-ages

Farmers Weekly. (2021, February 20). How to convert from colony to barn eggs and hit retail specs. (Jenkins, M.) Retrieved from: https://www.fwi.co.uk/livestock/poultry/how-to-convert-from-colony-to-barn-eggs-and- hit-retail-specs

Godley, A.C. & Williams, B. (2007). The chicken, the factory farm and the supermarket: the emergence of the modern poultry industry in Britain. Retrieved from: https://www.reading.ac.uk/web/files/management/050.pdf

Habig, C., Henning, M., Baulain, U., Jansen, S., Scholz, A.M. & Weigend, S. (2021). Keel Bone Damage in Laying Hens—Its Relation to Bone Mineral Density, Body Growth Rate and Laying Performance. Animals (Basel). 2021 Jun; 11(6): 1546. (2021, May 25). doi: 10.3390/ani11061546 Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8228274/

Hancock, S. (2020, November 12). Bird flu: Outbreak in Herefordshire triggers Britain-wide prevention zone - Six confirmed cases of virus in England this month. The Independent. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home- news/bird-flu-outbreak-herefordshire-b1721660.html

Hansard, UK Parliament. (2021, September). Hen Caging (Prohibition). Retrieved from: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2021-09-22/debates/3E79001A-C8B4- 4DD7-8877-DC8A1E15DD2D/HenCaging(Prohibition)

Hawthorne. E. (2016, August 20). Booker, Nisa and Spar Follow Mults in Pledge to Drop Caged Hen Eggs. Grocer.239(8269), 39.

Jansson, D. (2018). Gaining insights into the health of non-caged layer hens. Vet Rec. 182(12):347-349. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29572416/

Kyriakides, S. [SKyriakidesEU]. (2021, June 30). This is a historic day for animal welfare in [the EU]. 1.4 million united [voices] have asked us to #EndTheCageAge [Tweet]. Retrieved from: https://twitter.com/SKyriakidesEU/status/1410197648875864068

Lay Jr, D. C., Fulton, R.M., Hester, P.Y., Karcher, D.M., Kjaer, J.B., Mench, J.A.,

Mullens, B.A., Newberry, R.C., Nicol, R.C., O’Sullivan, N.P. & Porter, R.E. (2011). Hen welfare in different housing systems. Poultry Science, 90(1), 278-294. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032579119320875

McDermott, N. (2013, November 13). Free-range ISN’T better than factory-farmed: Why caged chickens have ‘less-stressed’ lives than their outdoor counterparts. Daily Mail. Retrieved from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2504766/Free- range-ISNT-better-factory-farmed-Why-caged-chickens-stressed-lives-outdoor- counterparts.html

National Geographic. (2015a, August 5). The Forgotten History of ‘Hen Fever’. (Rude, E.) Retrieved from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/the- forgotten-history-of-hen-fever

National Geographic. (2015b, August 6). Chickens and Eggs: From Queen Victoria to Bird Flu. (Weber, G). Retrieved from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/chickens-and-eggs-from-queen- victoria-to-bird-flu

NFU. (National Farmers Union). (n.d.). WORLD WAR ONE: THE FEW THAT FED THE MANY. Retrieved from: https://www.nfuonline.com/archive?treeid=33538

NHS. (2019, June 18). Osteoporosis. Retrieved from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/osteoporosis/

O’Carroll, L. (2019, Oct. 29). No-deal Brexit means return of battery eggs, farmers' union warns; NFU says government has ignored call for tariffs on cheap US imports from caged hens. The Guardian (London, England). Oct 29, 2019 ISSN: 0261-3077 Accession Number: edsgcl.607005047 Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/oct/29/no-deal-brexit-return-battery-eggs- farmers-union

Old Time Farm. (2021, March 24). Are Eggs Seasonal? Retrieved from: https://www.oldtime.farm/blogs/news/are-eggs-seasonal

Olsson, A., & Keeling, L. (2002). The push-door for measuring motivation in Hens: Laying hens are motivated to perch at night. Animal Welfare 11, 11-19. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/216131996_The_push-door_for_measuring_motivation_in_Hens_Laying_hens_are_motivated_to_perch_at_night

Poultry World. (2008). Sainsbury’s drops eggs from caged hens. Poultry World. 162(12), 8.

RSPCA. (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). (2005). The Case Against Cages. Retrieved from: https://www.rspca.org.uk/documents/1494935/9042554/Thecaseagainstcages+%285 13kb%29.pdf

RSPCA. (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). (n.d.a). Laying hens. Retrieved from: https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/farm/layinghens

Shepherd, J. (2016, July 30). Iceland and Morrisons to end sale of eggs from caged hens. Just-Food.com. 7/30/2016, p1-1. 1p. Retrieved from: https://www.just- food.com/news/iceland-and-morrisons-to-end-sale-of-eggs-from-caged-hens/

Stevenson, P. (2012). EUROPEAN UNION LEGISLATION ON THE WELFARE OF FARM ANIMALS. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/media/3818623/eu-law-on- the-welfare-of-farm-animals.pdf

Studer, H. (2001). How Switzerland got rid of battery cages. Retrieved from: https://www.upc-online.org/battery_hens/SwissHens.pdf

Sussex World. (2021, September 9). Henry Smith MP introduces Beatrice's Bill in the House of Commons. (Poole, M.) Retrieved from: https://www.sussexexpress.co.uk/news/politics/henry-smith-mp-introduces-beatrices- bill-in-the-house-of-commons-3394033

The Chicken Chick. (n.d.). BUMBLEFOOT in chickens: Causes and Treatment. Retrieved from: https://the-chicken-chick.com/bumblefoot-causes-treatment-warning/

The Guardian. (2002, June 25). Government floats plans to ban battery farming. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2002/jun/25/animalwelfare.world

The Scottish Farmer. (2021). HENS in an enriched cage (Pic: CIWF). Retrieved from: https://www.thescottishfarmer.co.uk/news/19173256.call-enriched-cages- laying-hens-phased/

UFAW. (Universities Federation for Animal Welfare). (n.d.). Keel Damage in Laying Hens. Retrieved from: www.ufaw.org.uk/why-ufaws-work-is-important/keel-damage- in-laying-hens

UK Parliament. (2022). Parliamentary Bills 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.parliament.uk/business/news/2022/

Webster, B. (2016, April 8). Asda may ban eggs from caged hens. The Times. 71879 (12).

Webster, B. (2017, Oct. 10). "Free-range firm's 4.3m caged hens." Times, 10 Oct. 2017, p. 7. The Times Digital Archive, link. gale.com/apps/doc/PGZKBW508281481/TTDA?u=ulh&sid=bookmark- TTDA&xid=b338d747.

White, K. (2016a, June 4). Aldi commits to phase out sale of eggs from caged hens by 2025. Grocer, 00174351, 6/4/2016 Grocer. June 4, 2016, Vol. 239 Issue 8258, p40, 1 p. By Kevin White.

White, K. (2016b, July 16). Tesco follows Aldi in committing to drop caged eggs by 2025 By Kevin White. Grocer. 7/16/2016, p73. 1p.

Bibliography

1900s.org.uk. (n.d.). Chickens and rabbits for meat and eggs in WW2 back garden. Retrieved from: https://www.1900s.org.uk/1940s50s-livestock.htm

ABC. (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). (2021, November 3). Australia was planning to phase out caged eggs by 2036, but one state is threatening to derail that. ABC Premium News (Australia).

Albert Schweitzer Foundation. (2021, April 12). Cages for Laying Hens Below 6% in Germany. Retrieved from: https://albertschweitzerfoundation.org/news/cages-for- laying-hens-below-6-in-germany

Animal Aid. (2016). The Battle of the Battery Cage. Retrieved from: https://www.animalaid.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/BatteryCage.pdf

Animals Australia. (2012, March 27). Battery cages banned in Europe. Retrieved from: https://animalsaustralia.org/latest-news/eu-bans-battery-hen-cages/

Appleby, M. (2003a). The EU Ban on Battery Cages: History and Prospects. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 6(2), pp.159-174. Retrieved from: https://www.humanesociety.org/sites/default/files/archive/assets/pdfs/hsp/soa_ii_cha p11.pdf

Appleby, M. (2003b). The European Union Ban on Conventional Cages for Laying Hens: History and Prospects. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 6(2), pp.103-121. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12909526/

Appleby, M. C., Duncan, E. T., & Hughes, B. O. (1991). Effect of perches in laying cages on welfare and production of hens. British Poultry Science, 33, 25-35. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00071669208417441

Arndt, M. (1932). Battery brooding; a complete exposition of the important facts concerning the successful operation and handling of the various types of battery brooders. (2nd ed.) Retrieved from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=coo.31924003197419&view=1up&seq=318

Australian Eggs. (2019, April). Effects of phasing out cage farming in Europe. Retrieved from: https://www.australianeggs.org.au/assets/dms-documents/Effects-of- phasing-out-cage-farming-in-Europe.pdf

Australian Eggs. (2021, 27 January). Assessing the carbon footprint of the egg industry. Retrieved from: https://www.australianeggs.org.au/what-we-do/leading- research/assessing-the-carbon-footprint-of-the-egg-industry

Australian Eggs. (2022). Egg farming systems: welfare science review. Retrieved from: https://www.australianeggs.org.au/what-we-do-/leading-research/egg-farming- systems-welfare-science-review

Baker, S.L., Robison, C.I., Karcher, D.M., Toscano, M.J., and Makagon, M.M. (2020). Keel impacts and associated behaviors in laying hens. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 222, p.104886. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168159119301467

BBC. (2014, October 15). 1939-45 The War Years by F. G. Imm. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/02/a8435702.shtml

BBC. (2021, June 30). Caged animal farming: EU aims to end practice by 2027. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-57668658

BHWT. (British Hen Welfare Trust). (n.d.a). Bumblefoot. Retrieved from: https://www.bhwt.org.uk/hen-health/health-problems/bumblefoot/

BHWT. (British Hen Welfare Trust). (n.d.b). Beak Trimming – Mutilation or a Necessity? Retrieved from: https://www.bhwt.org.uk/beak-trimming/

Bowers, J.K. (n.d.). British Agricultural Policy Since the Second World War. THE AGRICULTURAL HISTORY REVIEW p.66-76. Retrieved from: https://bahs.org.uk/AGHR/ARTICLES/33n1a7.pdf

British Lion Eggs. (2021). Industry Data. Retrieved from: https://www.egginfo.co.uk/egg-facts-and-figures/industry-information/data

Bulmer, E. & Gil, D. (2008). Chronic Stress in Battery Hens: Measuring Corticosterone in Laying Hens. International Journal of Poultry Science, 7(9), 880- 883, 2008. ISSN 1682-8356

Canter, L. (2016, July 9). Don't count your chickens … how restrictive covenants affect homebuyers. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/money/2016/jul/09/restrictive-covenants-homebuyers- out-of-pocket

CAWF. (Conservative Animal Welfare Foundation). (2020). Banning Cages for Laying Hens. (Bridgewater, G.) Retrieved from: https://www.conservativeanimalwelfarefoundation.org/resources/cawf-banning- cages-laying-hens-report-2020/

CAWF. (Conservative Animal Welfare Foundation). (2021, September 23). Hen Caging (Prohibition) Bill- Beatrice’s Bill. Retrieved from: https://www.conservativeanimalwelfarefoundation.org/end-cages-for-egg-laying- birds/cawf-patron-henry-smith-mp-brought-a-10-min-rule-bill-before-the-house-of- commons-to-end-cages-for-egg-laying-birds-the-bill-passed-its-first-reading-the- second-reading-will-be-held-on-oct-22nd-2/

CAWF. (Conservative Animal Welfare Foundation). (2022, February 1). Waitrose Supports Ending Cages for Laying Hens. Retrieved from: https://www.conservativeanimalwelfarefoundation.org/end-cages-for-egg-laying- birds/enry-smith-mp-led-the-hen-caging-prohibition-bill-known-as-beatrices-bill-after- the-rescue-hen-at-the-centre-of-a-campaign-coordinated-by-conservative-animal- welfare-fou/

Change.org. (2016). End the sales of eggs from caged hens in Tesco. Retrieved from: https://www.change.org/p/tesco-ban-the-sales-of-eggs-from-caged-and-barn- kept-hens

Change.org. (2019). Save the environment - Stop giving plastic toys with fast food kids meals. Retrieved from: https://www.change.org/p/burger-king-mcd-s-save-the- environment-stop-giving-plastic-toys-with-fast-food-kids-meals

Commission of the European Communities. (1996). Report of the Scientific Veterinary Committee, Animal Welfare Section on the welfare of laying hens, Brussels, 30 October 1996. Brussels.CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2007). ALTERNATIVES TO THE BARREN BATTERY CAGE FOR THE HOUSING OF

LAYING HENS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION. (Pickett, H.) Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/media/3818829/alternatives-to-the-barren-battery-cage-in- the-eu.pdf

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2012, March 1). The Life of: Laying hens. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/media/5235024/The-life-of-laying-hens.pdf

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2015, November 5). “AUF WIEDERSEHEN” CAGES. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/news/2015/11/auf-wiedersehen-cages

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2020, December 9). 88% OF UK PUBLIC THINK CAGES ARE CRUEL. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/news/2020/12/88-of-uk-public-think-cages-are-cruel

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (2021, June 30). EU ANNOUNCES HISTORIC CAGE BAN. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/news/2021/06/eu- announces-historic-cage-ban

CIWF. (Compassion in World Farming). (n.d.). LAYING HEN CASE STUDY AUSTRIA 1. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/media/3818841/laying-hen- case-study-austria.pdf

Countryside. (2021, February 18). Find out about the British egg sector. Retrieved from: https://www.countrysideonline.co.uk/food-and-farming/feeding-the-nation/eggs/

Daelnet. (2002, June 26). NFU wants “informed debate” on battery hens. Retrieved from: http://www.daelnet.co.uk/countrynews/archive/2002/country_news_26062002.cfm

Dalton, J. (2020, December 10). Bird flu: Chickens and hens must be kept indoors – but their meat and eggs may still be labelled ‘free-range’ - Experts warn stress of being cooped up may make creatures more vulnerable to viruses. The Independent. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/bird-flu-poultry- chicken-indoors-rspca-b1766540.html

Davies, J. (2016). Bird flu and consumer pressure: a global picture. 2016, Poultry World.

DEFRA. (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs). (2010). Poultry in the United Kingdom. The Genetic Resources of the National Flocks. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attach ment_data/file/69294/pb13451-uk-poultry-faw-101209.pdf

DEFRA. (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs). (2011). UK unites to stamp out battery cages. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk- unites-to-stamp-out-battery-cages

DEFRA. (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs). (2021). National statistics, Quarterly UK statistics about eggs - statistics notice (data to September 2021). Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/egg- statistics/quarterly-uk-statistics-about-eggs-statistics-notice-data-to-june- 2021#about-these-statistics

European Court of Auditors. (2018). Animal welfare in the EU: closing the gap between ambitious goals and practical implementation. Retrieved from: https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR18_31/SR_ANIMAL_WELFARE_EN.pdf

FAWC. (Farm Animal Welfare Council). (2009). Farm Animal Welfare in Great Britain: Past, Present and Future. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attach ment_data/file/319292/Farm_Animal_Welfare_in_Great_Britain_-_Past Present_and_Future.pdf

Farmers Weekly. (2014, April 11). Poultry production through the ages. Retrieved from: https://www.fwi.co.uk/livestock/poultry/poultry-production-through-the-ages

Farmers Weekly. (2021, February 20). How to convert from colony to barn eggs and hit retail specs. (Jenkins, M.) Retrieved from: https://www.fwi.co.uk/livestock/poultry/how-to-convert-from-colony-to-barn-eggs-and- hit-retail-specs

Glatz, P. & Pym, R. (2013). Poultry housing and management in developing countries. Poultry Development Review. p.29-63. ISBN 978-92-5-108067-2 (PDF) Retrieved from: https://www.fao.org/3/i3531e/i3531e.pdf

Godley, A.C. & Williams, B. (2007). The chicken, the factory farm and the supermarket: the emergence of the modern poultry industry in Britain. Retrieved from: https://www.reading.ac.uk/web/files/management/050.pdf

Habig, C., Henning, M., Baulain, U., Jansen, S., Scholz, A.M. & Weigend, S. (2021). Keel Bone Damage in Laying Hens—Its Relation to Bone Mineral Density, Body Growth Rate and Laying Performance. Animals (Basel). 2021 Jun; 11(6): 1546. (2021, May 25). doi: 10.3390/ani11061546 Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8228274/

Hancock, S. (2020, November 12). Bird flu: Outbreak in Herefordshire triggers Britain-wide prevention zone - Six confirmed cases of virus in England this month. The Independent. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home- news/bird-flu-outbreak-herefordshire-b1721660.html

Hansard, UK Parliament. (2021, September). Hen Caging (Prohibition). Retrieved from: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2021-09-22/debates/3E79001A-C8B4- 4DD7-8877-DC8A1E15DD2D/HenCaging(Prohibition)

Harrison, J. (2016, July 9). Queen Victoria Cochin Chinas. [Web log post]. Retrieved from: http://www.chickens.allotment-garden.org

Harrison, J. (n.d.). The Poultry Pages: Breeders & Suppliers of Live Poultry for Sale in Lincolnshire. Retrieved from: https://www.chickens.allotment-garden.org/poultry- suppliers/poultry-for-sale-Lincolnshire.php

Hartcher, K., & Jones, B. (2017). The welfare of layer hens in cage and cage-free housing systems. World's Poultry Science Journal. 73(4), 1-15. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320734228_The_welfare_of_layer_hens_in_cage_and_cage-free_housing_systems

Hawthorne. E. (2016, August 20). Booker, Nisa and Spar Follow Mults in Pledge to Drop Caged Hen Eggs. Grocer.239(8269), 39.

Institute of Agriculture & Trade Policy. (2013, March 26). How the Chicken of Tomorrow became the Chicken of the World. Retrieved from: https://www.iatp.org/blog/201303/how-the-chicken-of-tomorrow-became-the-chicken- of-the-world

Institution for European Environmental Policy. (2020). Assessment of environmental and socio-economic impacts of increased animal welfare standards.

TRANSITIONING TOWARDS CAGE-FREE FARMING IN THE EU. Retrieved from: https://ieep.eu/uploads/articles/attachments/5acf278b-c1b1-4e88-a14e- 6c5a4f04257a/Transitioning%20towards%20cage- free%20farming%20in%20the%20EU_Final%20report_October_web.pdf?v=637697 92427

Jansson, D. (2018, March 24). Gaining insights into the health of non-caged layer hens. Vet Rec. 182(12):347-349. Retrieved from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29572416/

Konkol, D., Popiela, E. & Korczyński, M., (2020). Animal Well-being and Behaviour. The effect of an enriched laying environment on welfare, performance, and egg quality parameters of laying hens kept in a cage system. 99(8), 3771-3776. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032579120302571

Kyriakides, S. [SKyriakidesEU]. (2021, June 30). This is a historic day for animal welfare in [the EU]. 1.4 million united [voices] have asked us to #EndTheCageAge [Tweet]. Retrieved from: https://twitter.com/SKyriakidesEU/status/1410197648875864068

Lay Jr, D.C., Fulton, R.M., Hester, P.Y., Karcher, D.M., Kjaer, J.B., Mench, J.A.,

Mullens, B.A., Newberry, R.C., Nicol, R.C., O’Sullivan, N.P. & Porter, R.E. (2011). Hen welfare in different housing systems. Poultry Science, 90(1), 278-294. Retrieved from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0032579119320875

McDermott, N. (2013, November 13). Free-range ISN’T better than factory-farmed: Why caged chickens have ‘less-stressed’ lives than their outdoor counterparts. Daily Mail. Retrieved from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2504766/Free- range-ISNT-better-factory-farmed-Why-caged-chickens-stressed-lives-outdoor- counterparts.html

National Geographic. (2015a, August 5). The Forgotten History of ‘Hen Fever’. (Rude, E). Retrieved from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/the- forgotten-history-of-hen-fever

National Geographic. (2015b, August 6.). Chickens and Eggs: From Queen Victoria to Bird Flu. (Weber, G). Retrieved from: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/chickens-and-eggs-from-queen- victoria-to-bird-flu

NFU. (National Farmers Union). (n.d.). WORLD WAR ONE: THE FEW THAT FED THE MANY. Retrieved from: https://www.nfuonline.com/archive?treeid=33538

NHS. (2019, June 18). Osteoporosis. Retrieved from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/osteoporosis/

O’Carroll, L. (2019, Oct. 29). No-deal Brexit means return of battery eggs, farmers' union warns; NFU says government has ignored call for tariffs on cheap US imports from caged hens. The Guardian (London, England). Oct 29, 2019 ISSN: 0261-3077 Accession Number: edsgcl.607005047 Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/oct/29/no-deal-brexit-return-battery-eggs- farmers-union

Old Time Farm. (2021, March 24). Are Eggs Seasonal? Retrieved from: https://www.oldtime.farm/blogs/news/are-eggs-seasonal

Olsson, A., & Keeling, L. (2002). The push-door for measuring motivation in Hens: Laying hens are motivated to perch at night. Animal Welfare 11, 11-19. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/216131996_The_push- door_for_measuring_motivation_in_Hens_Laying_hens_are_motivated_to_perch_at_night

Poultry World. (2008). Sainsbury’s drops eggs from caged hens. Poultry World. 162(12), 8.

RSPCA. (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). (2005). The Case Against Cages. Retrieved from: https://www.rspca.org.uk/documents/1494935/9042554/Thecaseagainstcages+%285 13kb%29.pdf

RSPCA. (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). (2020, March 2). What is beak trimming and why is it carried out? Retrieved from: https://kb.rspca.org.au/knowledge-base/what-is-beak-trimming-and-why-is-it-carried- out/

RSPCA. (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). (n.d.a). Laying hens. Retrieved from: https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/farm/layinghens

RSPCA. (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). (n.d.b). Laying hens - farming (egg production). Retrieved from: https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/farm/layinghens/farming

RSPCA. (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals). (n.d.c). Laying hens - key welfare issues. Retrieved from: https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/farm/layinghens/keyissues

Shepherd, J. (2016, July 30). Iceland and Morrisons to end sale of eggs from caged hens. Just-Food.com. 7/30/2016, p1-1. 1p. Retrieved from: https://www.just- food.com/news/iceland-and-morrisons-to-end-sale-of-eggs-from-caged-hens/

Spindler, H. (2020, May 20). WHAT’S OUR CAGE-FREE CAMPAIGN ALL ABOUT? Why we’re fighting for cage-free. The Humane League, UK. Retrieved from: https://thehumaneleague.org.uk/cages

Stevenson, P. (2012). EUROPEAN UNION LEGISLATION ON THE WELFARE OF FARM ANIMALS. Retrieved from: https://www.ciwf.org.uk/media/3818623/eu-law-on- the-welfare-of-farm-animals.pdf

Studer, H. (2001). How Switzerland got rid of battery cages. Retrieved from: https://www.upc-online.org/battery_hens/SwissHens.pdf

Sussex World. (2021, September 9). Henry Smith MP introduces Beatrice's Bill in the House of Commons. (Poole, M.) Retrieved from: https://www.sussexexpress.co.uk/news/politics/henry-smith-mp-introduces-beatrices- bill-in-the-house-of-commons-3394033

The Chicken Chick. (n.d.). BUMBLEFOOT in chickens: Causes and Treatment.

Retrieved from: https://the-chicken-chick.com/bumblefoot-causes-treatment-warning/

The Guardian. (2002, June 25). Government floats plans to ban battery farming. Retrieved from: http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2002/jun/25/animalwelfare.world

The Happy Chicken Coop. (2021, November 18). A History of Chickens: Then (1900) Vs Now (2022). Retrieved from: https://www.thehappychickencoop.com/a-history-of- chickens/

The Humane League. (2020, December 3). EVERYTHING YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT BATTERY CAGES. Retrieved from: https://thehumaneleague.org/article/battery-cages

The Law Commission. (2013). (LAW COM No 349) CONSERVATION

COVENANTS. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attach ment_data/file/322592/41070_HC_322_PRINT_READY.pdf

The Scottish Farmer. (2021). HENS in an enriched cage (Pic: CIWF). Retrieved from: https://www.thescottishfarmer.co.uk/news/19173256.call-enriched-cages- laying-hens-phased/

The Western Mail. (2003, March 24). Defra rejects pleas to ban all cages for egg- laying hens. Retrieved from: http://www.walesonline.co.uk/countryside-farming- news/country-farming-columnists/2003/03/24/defra-rejects-pleas-to-ban-all-cages- for-egg-layinghens-91466-12770432/

UFAW. (Universities Federation for Animal Welfare). (n.d.). Keel Damage in Laying Hens. Retrieved from: www.ufaw.org.uk/why-ufaws-work-is-important/keel-damage- in-laying-hens

UK Government - The Welfare of Battery Hens Regulations 1987. Retrieved from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1987/2020/made

UK Government - The Welfare of Farmed Animals (England) Regulations 2007. Retrieved from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2007/2078/contents/made

UK Parliament. (2021, September). Hen Caging (Prohibition). Retrieved from: https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/2021-09-22/debates/3E79001A-C8B4- 4DD7-8877-DC8A1E15DD2D/HenCaging(Prohibition)

UK Parliament. (2021). Hen Caging (Prohibition) Bill. Private Members' Bill (under the Ten Minute Rule). Retrieved from: https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3051/publications